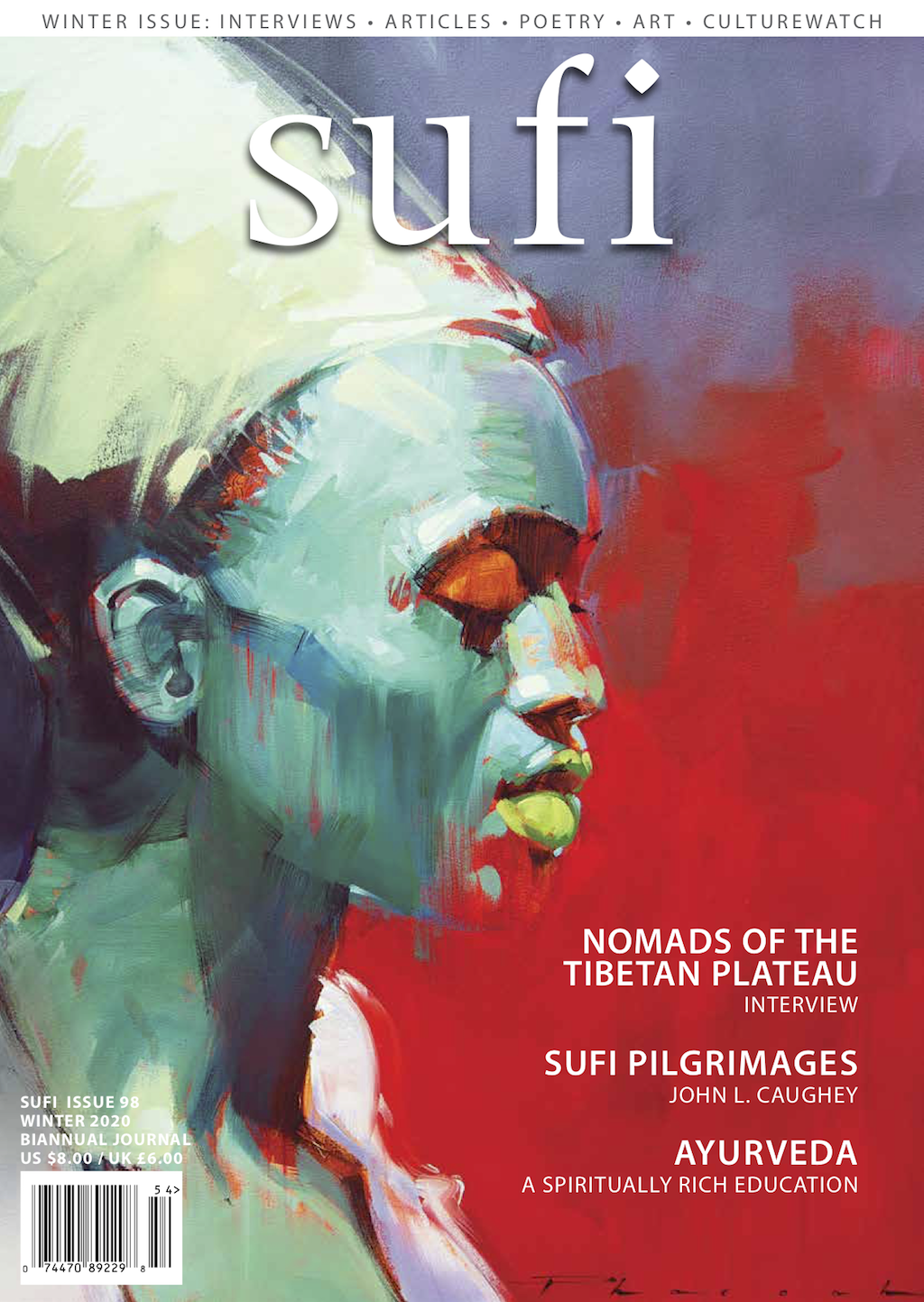

Nomads of the

Tibetan Plateau

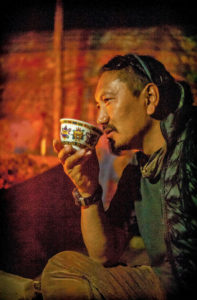

Interview with

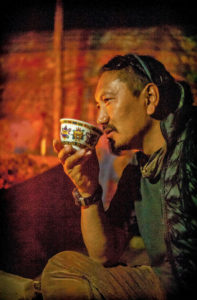

Trachung Kunchok Palsang

By Tracy Burnett and Tsering Dorje

For the past few years, we have had the privilege of interviewing nomads from different parts of the eastern Tibetan Plateau. Each nomad has spent a significant portion of his or her life herding or otherwise caring for yaks. Trachung Palsang has further created an environmental and cultural discussion center near his hometown, inclusive of food and rooms for tourists who come and supplement their travels with these healthy discussions. Palsang’s interwoven interests in nomadic life, literature, environmentalism and society helped him see straight to the heart of our questions about Tibetan nomadic life, and his answers are insightful, stimulating, and poetic. For six hours during summer 2019, he graciously shared his wisdom. We have done our best to select the most relevant excerpts of the interview for this journal and translate them faithfully to Palsang’s original words and meanings. We begin this journey with Palsang’s description of life on the grassland from before he left his hometown to attend school at the age of 14, and his musings on what he has seen changing within people since then.1 Yesterday, as the two of us were talking, one thing I said was, “Wherever there is real life, there is beauty.” If you want to experience life’s beauty, your heart must be attentive to real life.

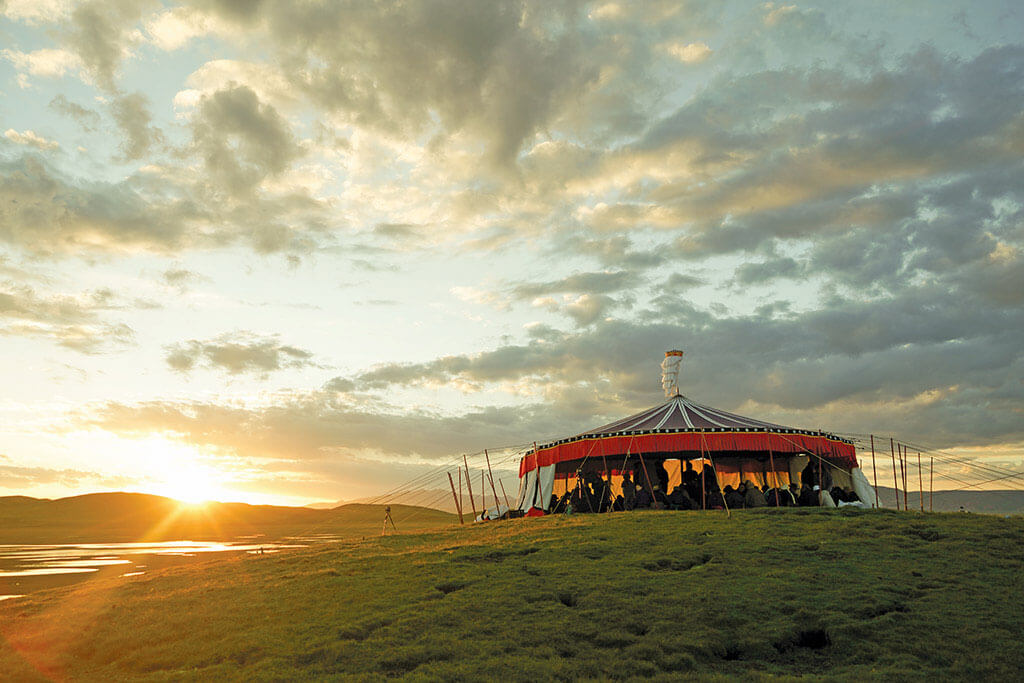

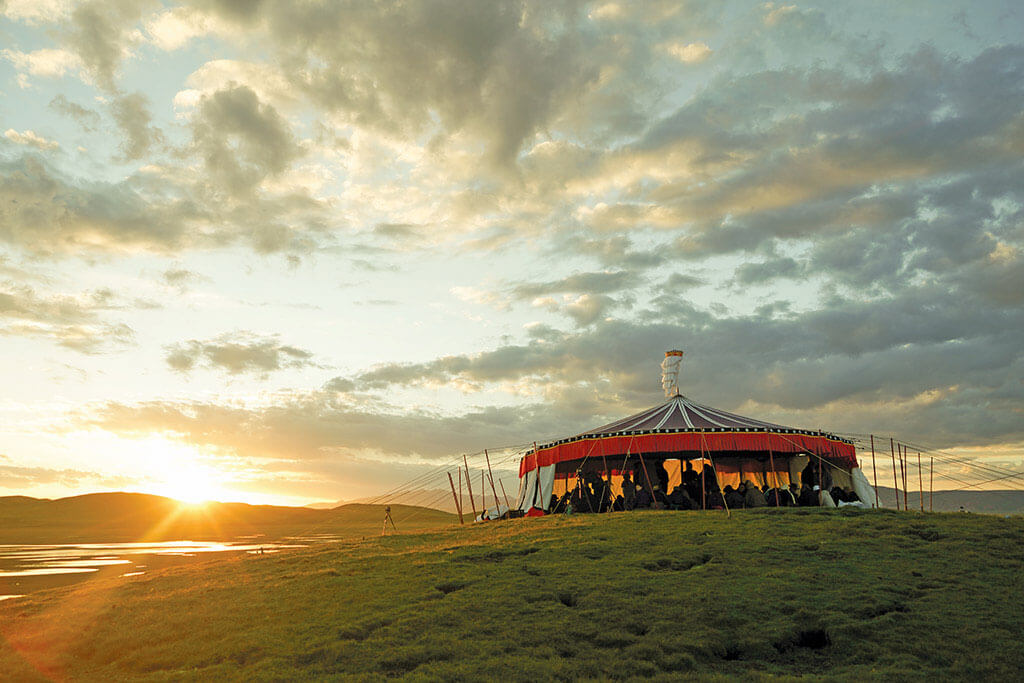

For example, within the society of my childhood herding livestock on the grassland, if people had stayed distracted by things such as looking at phones and staying in outside teahouses—like children these days do—I don’t think they would have had any chance to see the beauty. I think to myself, “In general these days, aren’t there very few nomads who see beauty within their own lives and livelihoods?” Something seems to be replacing it, and I wonder, “Could the most important thing be whether one’s heart is attentive to real life?” It is difficult to say exactly whether or not this is the case. For example, reflecting on a single couple, in the past, after breakfast, the men would herd their livestock to far-off pastures, eat on the grassland, and abide there in leisure. When they were coming back home in the evening, their wives for their part saw them coming, herding animals, accompanied by the murmuring of livestock beneath sunset’s blushing clouds. For one thing, they had been separated for the entire day. For another, the beauty of their husbands drawing near—their particular form; their appearance on their horse; the scene of them herding livestock—brought with it a feeling like hope.

For example, within the society of my childhood herding livestock on the grassland, if people had stayed distracted by things such as looking at phones and staying in outside teahouses—like children these days do—I don’t think they would have had any chance to see the beauty. I think to myself, “In general these days, aren’t there very few nomads who see beauty within their own lives and livelihoods?” Something seems to be replacing it, and I wonder, “Could the most important thing be whether one’s heart is attentive to real life?” It is difficult to say exactly whether or not this is the case. For example, reflecting on a single couple, in the past, after breakfast, the men would herd their livestock to far-off pastures, eat on the grassland, and abide there in leisure. When they were coming back home in the evening, their wives for their part saw them coming, herding animals, accompanied by the murmuring of livestock beneath sunset’s blushing clouds. For one thing, they had been separated for the entire day. For another, the beauty of their husbands drawing near—their particular form; their appearance on their horse; the scene of them herding livestock—brought with it a feeling like hope.

It was also like that whenever the women drew nearer, like when I used to see my mother. That also was beauty: black yak-hair tent, smoke, and there the motions of women at work carrying jugs of water or baskets for yak dung on their backs. The scene slowly came to embody what seemed like a movie. Then, when the couple gathered in their black yak-hair tent again—for example, when coming back from having gone outside and glanced around—and squeezed back close to the glowing light there, the light was the waving, blazing hearth fire of their black yak-hair tent. They would stretch up and down and sit, and if the husband told the stories of the day and the far-off pastures, they were all new. Really, from this, sometimes I think there is one hundred percent the semblance of romance. This is life; when not many people had interfered with the lifestyle of that time, it was an extremely delightful and good way to live. However, these days, a variety of things like phones have strong propensity to obscure the beauty-perceiving heart. “Once people cannot see beauty, has huge change arrived?” I wonder.

[wcm_restrict plans="Sufi Journal Digital Edition, Sufi Journal Digital Edition old"]

In this later excerpt, Palsang begins to explain how Tibetan nomads have traditionally co-composed the ecology of the Tibetan plateau grasslands, along with myriad companion animals and cultural beliefs. While opening the case for Tibetan nomadic society and cultural beliefs as essential aspects of local ecology, he describes how the Tibetan cultural conception of g.yang2 explicitly binds households’ prosperity and grassland ecosystems in support of one another via particular animal husbandry. He then demonstrates that the failing of nomads’ adherence to their cultural system is simultaneous with a breakdown of balance in local ecosystems. In terms of generating hope for the future, whereas in the first excerpt he called for the heart’s attentiveness to real life, Palsang here highlights yearning as fundamental to the grassland socio-ecology’s future health. With regard to the ecology of a grassland, if one says, “four

g.yang livestock,” then livestock are considered to be

g.yang. Perhaps this conception originated when an exceedingly discerning person came to understand an essential truth and changed them into

g.yang. Once the convention of calling them

g.yang was established, it seems that people’s hearts held more faith. What did the man come to understand? You can see that, generally speaking, horses, yaks, and sheep all eat grass. However, there are a few flowers and weeds that yaks will never eat; sheep eat them. Sheep will put pressure on them so they do not overpopulate. Some places have weeds that none of horses, yaks, nor sheep eat; they are noxious. When they sprout, goats go looking for them! They are like a meal’s red pepper, so goats like them. Goats put pressure on them so they do not overpopulate.

It is my speculation that, first, one person reached an extraordinary understanding of horses, yaks, goats, and sheep, then transformed it into faith by coining the phrase, “four g.yang livestock.” Adding g.yang to the phrase references the fact that, if these four livestock all stay on the grassland, in general the grassland will trend toward equilibrium. No matter how many kinds of plant species there are, it will be this way: two hundred, three hundred, or one hundred will be the same. As long as the four g.yang livestock keep the populations in moderation, then they will not increase and overpopulate. I think of it this way.

Take our thistle as an example. When thistles emerge, nothing else eats them; horses eat them. When they are full sometimes, I don’t know whether they eat them, but they eat them when they are hungry. Sometimes, really, when you are riding a horse and the horse is hungry and tired, to speak truthfully, this is his training; when he is hungry, he can eat many kinds of things.

Horses that are not hungry in the least, like horses these days, are like nomads who have been resettled: they do not do a lick of work. Therefore, milking yaks, riding horses and the like, can compose an ecological system. Each intertwines with the others, one and one. Looking at it this way, have horses contributed to the whole? What have yaks done for nomads? Also, what do sheep contribute to nomadic life—to life as a whole?

I explained it thusly before: when an elder man says, “I own the four g.yang livestock,”3 he says it as though there is nothing he could say that could be better. When he says it, in his voice there is a strength, and the resonance of his voice, his face’s lustre and the like, can’t be compared with anything from anywhere.

Then, to say, “I own horses, yaks, and sheep,” compared with before, is to have fallen to a slightly lower place. There is none of the faith that comes with the word g.yang, nor that deep strength. It is just a statement: “I am rich.” In contrast, the former expresses that I have reached a high place, and in addition to expressing that I have reached that height, it describes honor and good fortune in endeavors.

Taking it further, generally, when these days people say, “My sheep,” or “My yaks,” they fall to an even lower place. They return to the bare necessities of life. This is the level of mere calculation of whether or not their livelihood will go on.

Then, if I speak about land, I have none of horses, yaks, and sheep all three. I have only some land surrounded by a fence. “Can I profit from this land?”

Then, aren’t there some people who don’t even have land? They say, “Can I find a place to work?” It is as though the honor, karmic merit, state of mind and so forth of nomads are waning. If people were to recognize this and have the feeling that things are diminishing, that would be good. Right now, that is not the case; worse still, the situation is flipped on its head: people consider this to be progress and honor. Isn’t there peril in that?

Look, everything is upside-down these days. The greatest part of my greatest wish is wondering whether some hope lies within those people who have gone to school, glimpsed the world, met with difficulties, and come right back again. Why? Look how most of the people who post grassland, flowers, horses, yaks and sheep, and black yak-hair tents on the Internet are those who have learnt wisdom, traveled elsewhere, and stayed in many places. At the very least, they have yearning.

As to the character traits that Palsang holds in high esteem among those who yet co-constitute the grassland socio-ecosystem, being relaxed, having little fear, being resilient, giving of oneself to serve others, not harming others, taking part in the world, yet also acting in accord with one’s nature (or, perhaps, having the listed traits as one’s nature) take center stage. Of equal import is that each trait is exemplified not only within nomads, but also within the yaks and grasses with whom they live. Thinking in another way, the only animal—not a plant, but an animal—that does not damage the land at all is the yak. Animals like horses and sheep will use whatever means are necessary to eat, but yaks are incredible. It is not kindness; it is their karmic fate. “Khyung dkar mdzo have no upper front teeth,” it is said. They will not harm the grass’s roots even a little bit, not even to save their lives.4 Chewing cud that they made from the grass above ground, they die. At times, this is incredible.

We do not consider their worth. If we think in detail, it is like fate. Any way about it, this kind of land faces many difficulties. In a place such as this plateau, which can be very easily harmed, such an animal lives as will not damage it. When yaks are full, they simply sleep. Right? They are not like horses and sheep, which must roam passes and valleys day by day.

Also, it seems that yaks do not fear. They act according to their own minds, or just in relaxation, and never destroy even a bit of land. They are animals that can give up their lives instead of damaging land. I don’t know whether you two were present yesterday when we mentioned this proverb: “Where a Tibetan has spent a lifetime is left but a pile of ash.”5 The lifestyle of yaks is very similar to this line of thought. Think about it for yourself. “I would die to not hurt the land.” For others, “No matter how I live on the land, I am still one that digs into it with my horns.”5 But look, when digging into the land with their horns, there is not a single yak that cleaves into the waving grassland. They seek out black dirt or dry pits of sand to dig into with their horns.

“First, think about the yaks, then imagine a nomad elder with sun-tanned face and vitality, following his life along, singing songs, riding horses, explaining what is attractive in horses, and living according to his own world experience. From his mouth, he utters, ‘Where a Tibetan has spent a life time is left but a pile of ash.” What he calls “Tibetan,” I think refers to “nomad”; thus he can say, “Where a Tibetan has spent a lifetime is left but a pile of ash.” His line of thought is similar to the way that yaks behave. No matter where you have been or what you have done, you must have met with the sentiment. For example, these days, China’s highest leader Xi Jinping has been talking about golden and silver mountains.6 That saying and the Tibetan saying “golden fatherland” are one and the same; they have exactly the same meaning, right? People might even have been saying this before several thousands of years ago; I am not sure. Isn’t it the point of all of these sayings to talk about the natural environment?

I told you first about yaks and second about nomads. The third thing I will tell you about is our land’s grass culms, called rdzwa ‘jag ma. See, on this Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, there are exceedingly beautiful flowers, and they disappear in the winter. On the grassland, the worst dangers come during the winter; few people remain on the grassland then, so people are mostly familiar with the flowers from other times of year. Many people love and are kind to those flowers. Nobody at all looks at our grass culms. Nobody photographs them. Yet what have grass culms achieved? See, when the grasses and flowers of this Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau fade, the grass culms remain.

There are parts of our homeland where the wind blows extremely strong and can sometimes sway thick metal poles. As for grass culms, I have counted: when the winter winds blow them, they move about and I watch the time. How much do they move in one minute, or in half an hour? Throughout the winter months, they move like that. No matter how much they move, their roots never give way. Throughout the winter months, they stay like that. When animals are hungry, they come to eat them; if not, the grass culms stay sturdy. In the end, if no animals eat them at all, then in the spring, when the green grass grows, they will start to slowly collapse and become so-called fertilizer. So, you see: nobody especially notices black yaks, nomads, and grass culms, but they are the greatest contributors. It is really this way, exactly. Who notices them? Nobody notices them, yet what they contribute is incredible. For this reason, it is sometimes difficult to put into words.

It is possible, when people talk about how valuable yaks are, that they say, “Yaks deserve my gratitude.” They say, “Yaks deserve people’s gratitude.” Don’t they say that? Isn’t it said that it was from being nourished by yaks that this ‘Tibet, Land of Snow,’ came to be? But the value of yaks is not a simple matter of Tibet, the Land of Snow. There is yet ecology. There is yet the yaks’ own countenance and character. Look: They can live in as cold a place as this. It seems that that they don’t have any fear, and they have such a gentle disposition. It is difficult to explain, but for those reasons—from the standpoint of their way of life—they would rather slowly offer forth their lives than dig into the land. Karmic fate delivered them this way.

One day, while I was sitting with a lama from Khams7 who says that Tibetans must take pride in their ethnic heritage, he complained, “Nowadays, nomads do not pitch black yak-hair tents.” His tone of voice carried such high regard for black yak-hair tents that I asked, “A lags,8 what is this about? What’s good about pitching black yak-hair tents?” He replied, “It is a feature of Tibet.”

I don’t think it is like that at all. If you just call it a feature, then it is not an important object at all. What does that feature need to do? If you look at that feature, perhaps it is beautiful; if somebody else looks at it, it has no certain beauty. Now, if you need to talk about its value, you need to talk about different values than that. It is like a facet of nature. It is like a facet of lifestyle. For instance, even were new circumstances to come to the world, I would not be cold, right? I have the skill for dealing with it. I can cut the yaks’ hair and make a black yak-hair tent. No matter how cold people around the world get, I can take care of myself. This is one thing.

Second, you don’t need to depend at all on outside resources. For example, from factories and the like, even the best cloth requires environmental impact like cutting trees and releasing pollution. After the production, dye is applied. Once it undergoes all of the processes, it has finally become cloth, and even that cloth will one day break.

From the standpoint of one’s lifestyle, when there is the black tent, there is more work. People generally get sick if they live carelessly; for that reason, you need to move, and you also need to move your brain. Also, when nomads weave, now and then they need to pause and move their brains: “Over here, I connected this one. Oh, not this one; I connected that one,” and so on and so forth. Isn’t that life? Therefore, if you use the black yak-hair tent, you don’t need to depend at all on anything external. You can do it yourself.

Furthermore, within this, what I am saying is that by using the tent system of cutting wool, making a tent, pitching the tent and living with the tent, I do not the least bit harm the nature that people these days say the world needs as much as a living body needs an eye. Even if I do not benefit it, I do not harm it. This is me.

As exemplified by yaks, grass culms, and traditional nomads in Palsang’s view, it is important not to harm the natural world. In the Tibetan nomadic social-ecological system, each element interweaves with the others, for it is valued and cared for by them. This is what Palsang is referring to when, at the end of the following excerpt, he refers to different elements of the natural environment, saying, “This already has a caretaker!” But what happens when a society divides elements of the natural world from their caretakers who valued and used them? The following excerpt furnishes a Tibetan cultural lesson that can weave humans into their natural environment and contrasts it with examples from other cultures in which humans are separated out. No longer immediately dependent on the natural environment, they are no longer integrated into its system. Following Palsang’s logic to a point, we must wonder: once humans remove themselves from the natural system, is it possible for them to protect it any longer? You know Kirti Rinpoche’s Second Teachings, right?9 They hold an essential truth. When butchering animals, don’t people have compassion and chant scriptures? They do. Sometimes, seeing it with their own eyes, they sit in recitation feeling compassion for the animals; from this, they experience a kind of apprehension, thinking, “No matter what the animal, it is alive and living.” This is from culture.

As exemplified by yaks, grass culms, and traditional nomads in Palsang’s view, it is important not to harm the natural world. In the Tibetan nomadic social-ecological system, each element interweaves with the others, for it is valued and cared for by them. This is what Palsang is referring to when, at the end of the following excerpt, he refers to different elements of the natural environment, saying, “This already has a caretaker!” But what happens when a society divides elements of the natural world from their caretakers who valued and used them? The following excerpt furnishes a Tibetan cultural lesson that can weave humans into their natural environment and contrasts it with examples from other cultures in which humans are separated out. No longer immediately dependent on the natural environment, they are no longer integrated into its system. Following Palsang’s logic to a point, we must wonder: once humans remove themselves from the natural system, is it possible for them to protect it any longer? You know Kirti Rinpoche’s Second Teachings, right?9 They hold an essential truth. When butchering animals, don’t people have compassion and chant scriptures? They do. Sometimes, seeing it with their own eyes, they sit in recitation feeling compassion for the animals; from this, they experience a kind of apprehension, thinking, “No matter what the animal, it is alive and living.” This is from culture.

In some places, killing an animal produces no feeling whatsoever; they are just meat. Isn’t that right? In some places, they are pets; not doing any work, they are babied.

From our standpoint, they are neither pets nor pieces of meat; while my heart is saying, “For my livelihood, I have no way not to kill this animal,” from my heart I am chanting scriptures, and I am anointing the animal with blessed water. This is culture. If culture is anything, it is this.

If this disappears, and all of our meat becomes purchased from the market, then, within that transition, like wood being chopped,10 animals will become meat pieces. Then the culture will be gone. Generations to come will say, “I won’t harvest meat myself,” and instead they will take it processed by machines. . .

Let me give you an example. One time—I will never forget this in my entire life—I rose from my bed and, as I was rushing through the doorway, my family member Mgon rnam11 appeared in it. Like this, our heads crashed into each other—although generally Mgon rnam is big, at that time we were a similar size—so we fought. Suddenly, somebody slapped my cheek! What looked like fire sparks colored my vision. Our father, pulling me from my brother, spoke: “In this time when I am struggling to feed you, you dare to roughhouse here?”

Not in the least could I understand that I had done anything wrong. I thought, “There is no reason in this,” but I didn’t dare to say so. Now, when I think about it, it was education. Really. ‘I am struggling to nourish you, ending an animal’s life right here to provide food for all of us, and yet you clamor! Although you are not even reciting ma ni,12 yet you must not make a racket.’ Isn’t that the case? Now that is culture.

In that way, sometimes, if we think leisurely, what we exactly need is among all of that. Seemingly there, but also seemingly not, it is what we call “culture.” What’s more, one hundred percent of people have a method of eating. No matter what they do, they can eat. No matter what they do, they can wear clothes. Sliding bugs sustain themselves; flying birds sustain themselves; whatever you do, something will come of it. But regardless of that, these days, some lamas have gone over and above to say this or that about protecting the natural environment and grasslands. This already has a caretaker! One hundred percent, someone is caring for water; someone is caring for grass; someone is also caring for trees. Each one has its own value. But we have something between all of these. As for that, in truth, I don’t know whether there is someone to care for it or not.

While each caretaker simultaneously protects that element of nature which he values, perhaps culture takes responsibility for protecting the interwoven, multi-dimensional balance of all of the elements in concert. In this pointed, poignant final excerpt, Palsang flourishes the livestock of past, present and future as the masterpiece of nomads, painted on the canvas of culture, and it is difficult to imagine that he is not enjoining us to live with such abundance as they have lived. We offer the exceptionally beautiful yaks to join protector deities’ herds. We make these beautiful offerings firstly as praise for the celestial entities and secondly because, this way, beautiful livestock will adorn our herds.13 In this regard, these days the nomadic experience of life has really become more like that of the Hui and Han people.14 Animals are counted with food and money in mind. Until recently, it wasn’t like this: animals of beautiful form and color, taken altogether, were an eternal composition, a book that would not end. Three Jewels.15 Taking as demonstration someone who loves horses very much, a horse eating grass sounds, to him, the same as song. Really. The experience of riding a horse as it steps along and the impression of herding yaks are like music. Doesn’t each have its own unique feel?

While each caretaker simultaneously protects that element of nature which he values, perhaps culture takes responsibility for protecting the interwoven, multi-dimensional balance of all of the elements in concert. In this pointed, poignant final excerpt, Palsang flourishes the livestock of past, present and future as the masterpiece of nomads, painted on the canvas of culture, and it is difficult to imagine that he is not enjoining us to live with such abundance as they have lived. We offer the exceptionally beautiful yaks to join protector deities’ herds. We make these beautiful offerings firstly as praise for the celestial entities and secondly because, this way, beautiful livestock will adorn our herds.13 In this regard, these days the nomadic experience of life has really become more like that of the Hui and Han people.14 Animals are counted with food and money in mind. Until recently, it wasn’t like this: animals of beautiful form and color, taken altogether, were an eternal composition, a book that would not end. Three Jewels.15 Taking as demonstration someone who loves horses very much, a horse eating grass sounds, to him, the same as song. Really. The experience of riding a horse as it steps along and the impression of herding yaks are like music. Doesn’t each have its own unique feel?

Once all of these have gone away, people will think, “One sgor mo, two sgor mo, three—,”16 and the skills of our life will have been cast away. Beauty will have been cast away. Once all of them have been cast away, you will be a beggar with nothing more than money in your hand. Isn’t that right? You will have fallen to the state of a person whose stomach is full, but whose mind wants. Anyway, these days, perhaps what we have cast aside is not yaks and sheep but rather beauty, value, and our standpoint on values.

NOTES

1 The Tibetan norm of age calculation is to consider a baby one year old when it is born, two years old at the next New Year celebration, three years old at the following New Year celebration, and so forth. Palsang was born in the 1970s.

2 g.yang is an intangible, fluid household asset that lends efficacy to domestic endeavors.

3 The four g.yang livestock are horses, goats, yak and sheep.

4 Yaks and other ruminants have a dental pad in place of upper incisors, making it difficult for them to pull up plants by the roots.

5 The second part of the proverb was not mentioned during this interview: “Chinese people put a fortress where they stay but a single day.”

6 Xi Jinping, President of the People’s Republic of China since 2013, has said on multiple occasions that “clear rivers and green mountains are akin to mountains of silver and gold.”

7 Khams refers to the southeastern region of the Tibetan Plateau.

8 A lags is a respectful form of address for certain religious figures within Tibetan Buddhism.

9 Kirti Rinpoche founded Kirti Monastery, one branch of which is the local monastery of Palsang’s hometown.

10 This is symbolic of an irreversible action.

11 Mgon rnam is Palsang’s brother.

12 ma ni is an abbreviation for oM ma Ni pad+me hU~M, a ubiquitous Tibetan Buddhist mantra.

13 Although a livestock that is offered to a protector deity theoretically joins that deity’s herd, it may physically remain in the herd to which it previously belonged.

14 Hui refers to an ethnic minority of China, and Han refers to the ethnic majority of China.

15 “Three Jewels” is an exclamation calling on Buddha, dharma, and sangha.

16 sgor mo is the Tibetan word for denominating money.

[/wcm_restrict]

PHOTOS © DIANE BARKER

[wcm_restrict plans="Sufi Journal Digital Edition, Sufi Journal Digital Edition old"]

RETURN TO ISSUE 98 TABLE OF CONTENTS

[/wcm_restrict]

[wcm_nonmember]

To read this article in full, you must Buy Digital Subscription, or log in if you are a subscriber.

[/wcm_nonmember]

For example, within the society of my childhood herding livestock on the grassland, if people had stayed distracted by things such as looking at phones and staying in outside teahouses—like children these days do—I don’t think they would have had any chance to see the beauty. I think to myself, “In general these days, aren’t there very few nomads who see beauty within their own lives and livelihoods?” Something seems to be replacing it, and I wonder, “Could the most important thing be whether one’s heart is attentive to real life?” It is difficult to say exactly whether or not this is the case. For example, reflecting on a single couple, in the past, after breakfast, the men would herd their livestock to far-off pastures, eat on the grassland, and abide there in leisure. When they were coming back home in the evening, their wives for their part saw them coming, herding animals, accompanied by the murmuring of livestock beneath sunset’s blushing clouds. For one thing, they had been separated for the entire day. For another, the beauty of their husbands drawing near—their particular form; their appearance on their horse; the scene of them herding livestock—brought with it a feeling like hope.

For example, within the society of my childhood herding livestock on the grassland, if people had stayed distracted by things such as looking at phones and staying in outside teahouses—like children these days do—I don’t think they would have had any chance to see the beauty. I think to myself, “In general these days, aren’t there very few nomads who see beauty within their own lives and livelihoods?” Something seems to be replacing it, and I wonder, “Could the most important thing be whether one’s heart is attentive to real life?” It is difficult to say exactly whether or not this is the case. For example, reflecting on a single couple, in the past, after breakfast, the men would herd their livestock to far-off pastures, eat on the grassland, and abide there in leisure. When they were coming back home in the evening, their wives for their part saw them coming, herding animals, accompanied by the murmuring of livestock beneath sunset’s blushing clouds. For one thing, they had been separated for the entire day. For another, the beauty of their husbands drawing near—their particular form; their appearance on their horse; the scene of them herding livestock—brought with it a feeling like hope. As exemplified by yaks, grass culms, and traditional nomads in Palsang’s view, it is important not to harm the natural world. In the Tibetan nomadic social-ecological system, each element interweaves with the others, for it is valued and cared for by them. This is what Palsang is referring to when, at the end of the following excerpt, he refers to different elements of the natural environment, saying, “This already has a caretaker!” But what happens when a society divides elements of the natural world from their caretakers who valued and used them? The following excerpt furnishes a Tibetan cultural lesson that can weave humans into their natural environment and contrasts it with examples from other cultures in which humans are separated out. No longer immediately dependent on the natural environment, they are no longer integrated into its system. Following Palsang’s logic to a point, we must wonder: once humans remove themselves from the natural system, is it possible for them to protect it any longer? You know Kirti Rinpoche’s Second Teachings, right?9 They hold an essential truth. When butchering animals, don’t people have compassion and chant scriptures? They do. Sometimes, seeing it with their own eyes, they sit in recitation feeling compassion for the animals; from this, they experience a kind of apprehension, thinking, “No matter what the animal, it is alive and living.” This is from culture.

As exemplified by yaks, grass culms, and traditional nomads in Palsang’s view, it is important not to harm the natural world. In the Tibetan nomadic social-ecological system, each element interweaves with the others, for it is valued and cared for by them. This is what Palsang is referring to when, at the end of the following excerpt, he refers to different elements of the natural environment, saying, “This already has a caretaker!” But what happens when a society divides elements of the natural world from their caretakers who valued and used them? The following excerpt furnishes a Tibetan cultural lesson that can weave humans into their natural environment and contrasts it with examples from other cultures in which humans are separated out. No longer immediately dependent on the natural environment, they are no longer integrated into its system. Following Palsang’s logic to a point, we must wonder: once humans remove themselves from the natural system, is it possible for them to protect it any longer? You know Kirti Rinpoche’s Second Teachings, right?9 They hold an essential truth. When butchering animals, don’t people have compassion and chant scriptures? They do. Sometimes, seeing it with their own eyes, they sit in recitation feeling compassion for the animals; from this, they experience a kind of apprehension, thinking, “No matter what the animal, it is alive and living.” This is from culture. While each caretaker simultaneously protects that element of nature which he values, perhaps culture takes responsibility for protecting the interwoven, multi-dimensional balance of all of the elements in concert. In this pointed, poignant final excerpt, Palsang flourishes the livestock of past, present and future as the masterpiece of nomads, painted on the canvas of culture, and it is difficult to imagine that he is not enjoining us to live with such abundance as they have lived. We offer the exceptionally beautiful yaks to join protector deities’ herds. We make these beautiful offerings firstly as praise for the celestial entities and secondly because, this way, beautiful livestock will adorn our herds.13 In this regard, these days the nomadic experience of life has really become more like that of the Hui and Han people.14 Animals are counted with food and money in mind. Until recently, it wasn’t like this: animals of beautiful form and color, taken altogether, were an eternal composition, a book that would not end. Three Jewels.15 Taking as demonstration someone who loves horses very much, a horse eating grass sounds, to him, the same as song. Really. The experience of riding a horse as it steps along and the impression of herding yaks are like music. Doesn’t each have its own unique feel?

While each caretaker simultaneously protects that element of nature which he values, perhaps culture takes responsibility for protecting the interwoven, multi-dimensional balance of all of the elements in concert. In this pointed, poignant final excerpt, Palsang flourishes the livestock of past, present and future as the masterpiece of nomads, painted on the canvas of culture, and it is difficult to imagine that he is not enjoining us to live with such abundance as they have lived. We offer the exceptionally beautiful yaks to join protector deities’ herds. We make these beautiful offerings firstly as praise for the celestial entities and secondly because, this way, beautiful livestock will adorn our herds.13 In this regard, these days the nomadic experience of life has really become more like that of the Hui and Han people.14 Animals are counted with food and money in mind. Until recently, it wasn’t like this: animals of beautiful form and color, taken altogether, were an eternal composition, a book that would not end. Three Jewels.15 Taking as demonstration someone who loves horses very much, a horse eating grass sounds, to him, the same as song. Really. The experience of riding a horse as it steps along and the impression of herding yaks are like music. Doesn’t each have its own unique feel?