Heart of the Matter

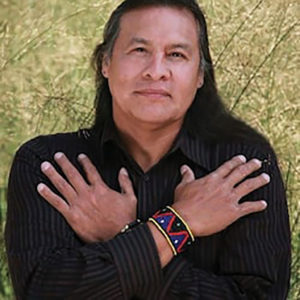

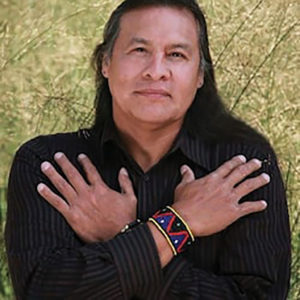

An Interview with Tiokasin Ghosthorse

Interviewed by Sholeh Johnston

In the seclusion of the northern Pennines in England, a group of forty people gather around a cozy fireplace in silence. The paper and kindling crackle in the flames, and our esteemed guest speaker, Tiokasin Ghosthorse, lifts a pinch of tobacco from his pouch, feeding it to the fire. It is a subtle and meaningful act, though we cannot yet explain why. It is felt. Tiokasin settles into his chair, looks up at us all with a warm smile, and begins.

“Imagine a language without ‘I’ without the concept of death, or mystery. Can you imagine it? You are now speaking Lakota.” Minds bend attempting to comprehend this possibility. He asks us all to write for ten minutes about ourselves, without using the words “I,” “me,” “my” or “mine.” In the sentences that emerge, the most apparent thing is relationship—to each other and the complex and mysterious web of life around us. “What if, when we are outdoors, we are really inside?” he asks. The simplicity of the lesson is profound, and exemplary of Tiokasin’s teaching—rooted, sincere, authentic, beyond the individual.

He never once mentions his accolades in the two days of teaching, but Tiokasin’s life is a vibrant tapestry of activism and advocacy for peace and the Indigenous Mother Earth perspective. A member of the Cheyenne River Lakota Nation of South Dakota, he is a survivor of the “Reign of Terror” from 1972 to 1976 on the Pine Ridge, Cheyenne River and Rosebud Lakota Reservations in South Dakota, and the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs Boarding and Church Missionary School systems designed to “kill the Indian and save the man.”

[wcm_restrict plans="Sufi Journal Digital Edition, Sufi Journal Digital Edition old"]

As a teenager, he spoke as the “voice of his people” at the United Nations, and ever since he has been educating people who live on Turtle Island (North America) and abroad about the importance of living with Mother Earth, most regularly as the Founder, Host and Executive Producer of “First Voices Radio,” a one-hour live program offering a platform to Native cultures from around the world.

His ability to bridge the Indigenous way of life with contemporary America arises from his own experience of pursuing a career in computing, but becoming increasingly uneasy with the culture of materialism that surrounded him. In his search for meaning, he returned to his roots and committed himself to reviving the “old ways” of his people, exchanging material wealth for community and the wellbeing of living in reciprocity with the land and other life forms.

Tiokasin is a 2016 Nobel Peace Prize nominee of the International Institute of Peace Studies and Global Philosophy, and a guest faculty member at Yale University’s School of Divinity, Ecology and Forestry where he focuses on the cosmology, diversity and perspectives on the relational/egalitarian vs. rational/hierarchal thinking processes of Western society. A master musician, he also performs worldwide, and has been a major figure in preserving and reviving the cedar wood flute tradition, using instruments crafted by his own hands.

Tiokasin’s spiritual activism represents an immediate and fundamental solution to the divide between human society and the environment: a humble acknowledgement of the ancient intelligence that exists within nature. His call to action is to re-learn the languages of life, so that we can commune with consciousness.

Your activism is about raising awareness of the Mother Earth Perspective. I remember at the Spiritual Ecology retreat where we met, you spoke of asking the land what to say before you give a workshop. Can you tell us more about this practice? That time in the North Pennines, the feel of the country was great. When I first arrived I didn’t say hello to anybody and I didn’t want to, because the first instruction is to go to the land and ask the land what it wants us to say as messengers. We’ve been neglecting Mother Earth, moving too far away from that which is obvious—that which gives us protection, nourishment and dreams. When I ask, it’s not with the expectation to receive an answer, but in acknowledgment that Mother Earth has been missing from the human mind. We think that we’re the only ones who can think and feel alive, but we have to take a step back and look to the great intelligence offered by relationship—the relational values of a rock understanding the fire, the fire understanding the water, the water understanding the trees and the animals understanding the sun, and so on.

To recognize this relational value we have to understand what’s going on “now.” If we don’t have the language of “now,” we’re stuck in the past or planning the future. As Natives, at least in the Western hemisphere, we ask, we don’t plan the future because we know we can’t plan Mother Earth—she’s already planned us, in the sense that she’s given all these intelligences, these conscious elements to ask from. When we go to the land, we understand we’re walking amongst elders.

When you’re coming from a people that have spoken these earth languages forever, and have not lost communication with the elements, then intelligence comes through and we understand what is to be said without forming any thought process. And once you’re finished asking, you offer something—in our way, we put tobacco down, or ask if we can put tobacco down, because every terrain is different, everything has already been placed there in balance by Mother Earth, and human beings can upset it by planning and moving and forcing, taking it all for granted. When I do this I’m recognizing the powers of all these consciousnesses that come through all of us. When we sit in our circles, like we did in the North Pennines, that’s what was coming through. It wasn’t me and my formulated ideas or thinking patterns. The messages are coming from the earth. It doesn’t mean I’m a shaman or anything like that—to think that I have a personal power because I identify with Mother Earth is not the point. It’s that you ask Mother Earth to be with you when you speak. I spoke to people such as yourself with that asking energy.

The motion of asking is not praying. When you pray it’s like begging the one who’s holding the bread for a piece of bread. But if you ask without a sense of lack, you can know what it is to be a “magi.” A “magi” is not a genie or something with special powers, it is someone or something that uses the Earth’s tools intelligently, in balance. The bird uses the wind to fly, and fire and water combine to make the wind.

In Sufism there’s a large emphasis on the heart as an alternative tool of perception—similar to what you say about broadening our awareness and tuning in to the way that the Earth and the different manifestations of consciousness speak to and through us. What is the role of the heart in your tradition? The word that we have for heart, chante, is not a noun, it’s a moving energy. It’s creating thoughts and feelings together. It also keeps our circulatory tree, in a sense —our brain, our nervous system, the blood or menea (the water) within our veins—moving. So, “Chan” means tree, or “tree-ing” if you put it in motion, and “te” is a derivative of “living,” so we are talking about “living tree-ing”—chante— when we speak of the heart.

A tree begins growing beneath the earth as a seed, and has to become knowledgeable about hydration and geology and nutrition of the minerals it picks up. To do this, the seed has to ask first, it has to give recognition that it’s in the ground, in the womb of Mother Earth. Then there is a flash of light, and the conscious seed is allowed to put down its roots and grow deeper into the consciousness of the earth. The tree keeps growing and learns the relational value that the only way it can survive is by learning to give off oxygen while taking in the waste products of those who breathe like mammals. It becomes a magi. It grows and grows, and its consciousness gives food in the form of fruit or seeds, or provides a place of harbor for animals or birds. It grows to understand the weather patterns, the winds, the seasons, the daylight and the nighttime, so it’s in balance. Every time it moves it’s in balance. Sometimes trees are four, five, six thousand years old. Trees are our elders. They are part of who we are, in our hearts. That’s why we called it “living tree-ing.”

The tree consciousness is a language of the earth, and cannot be destroyed because it is invincible. The wind is the wind, a rock is a rock, and all languages can describe this but they forget the sacred value that life is in motion. A tree is tree-ing, not just an objective form, and the heart has its own language too. In the modern world, it’s almost like we’re developing bigger languages because we’ve forgotten the basic, invincible languages—we don’t know what it is to have a “heart language” because we’ve taken it from the heart and put it into the mind. We are disconnected from the reality that we see with our senses. The trees, rocks, and all these elements live within us, and when your consciousness is all of those things then there’s always so much to learn by watching nature in movement.

Nature humbles you, it is the most powerful place to be because all that knowledge is in front of you, but it takes time to learn it, maybe generations. As Native peoples we’ve done that. We’ve been settled, we are advanced. We don’t even know what primitive is; the intelligence that’s in front of us in all life forms, that’s what I would call high intelligence.

Everything you’re saying reflects the idea in Sufism of returning to unity with an “absolute being” and stepping out of the “I” mindset. As I understand it, the concept of individualism doesn’t exist in your language. Could you say more about this? Yeah, in English we describe living amongst the community of Earth from the human perspective and that community is usually extracting from the Earth. That’s what makes individuals out of us, the “I” language, if you will. “I” is a noun or a pronoun that is singular, alone. It refers to self, to being individual. You have power or you don’t have power as an individual, so therefore you’re either looking for domination or lacking domination so to speak. In the “we” language that Lakota speak, “I” doesn’t exist. In the long-ago language before the colonials arrived here in the Western hemisphere “we” was more important, and is still in practice among the Native people. “I, me, my” or “mine” doesn’t exist in the language. To us, “I” is a verb. You are always in motion and if you are always in motion then your language is always relational, you’re describing things in a moving relationship to the matrix of life, and there’s no control or domination whatsoever. And that’s kind of alarming to the Western world—people want to control the environment so we make up words for nature, we give Latin names to life. But most of life doesn’t understand individualism, it’s a box which people are trying to find their way out of.

Imagine you set something like a cup in front of you, and you write “mystery” on a piece of paper, and tape it to the cup, and say “that’s mystery.” It’s a container, a preconceived notion of what mystery is, just like that. We “nounify” it, we “thingify” mystery. We say, “it’s a mystery, it’s unknown, it’s fear, there’s no answer to it,” but we still want to have control of mystery. We want to solve mystery. In the Western world, people are going crazy trying to solve the problem of mystery. They can say, well, that’s mystery over there and that mystery is making us go crazy. The other way of understanding mystery, using the “we” language, is that you take the cup away. Once you remove it, where is mystery? Where does mystery exist? Can we even ask how mystery is not there? That blows the box apart because we can’t contain mystery, we can’t even name it “mystery.” We can’t even say, “that’s God.” We can’t say, “that’s divine.” People who are not trying to control mystery, who are accepting mystery as it is, experience it as infinite.

We’re forgetting that “I” is a verb, in motion. You can’t capture that “I,” and that’s really freeing. It’s freeing when you can no longer say “that cup is mystery.” Or you can no longer say “that’s a cup” [chuckles].

When you’re watching this movement of the universe you see that you can’t really control anything. You know no one is in charge.

This reminds me of the metaphor in Sufism and Persian poetry of spiritual surrender and the experience of the divine as madness, because of the irrationality of the experience. How can we find balance with surrender and trust in mystery without understanding it in the mind? To the Western mind, if something doesn’t fit in the box it’s not of any use. Balancing the positive with the negative is impossible to think of in relational “we” languages because there is no positive or negative, no binary. That’s just our need for a scientific explanation about how spirit’s supposed to be, or we get religious about our spirituality and we begin to put rules upon it. There’s no movement, it’s a mindset that’s been preoccupying Western thinkers for maybe three, four thousand years.

People feel depressed because they can’t have power, they’re not getting enough money, they’re not good enough, not pretty enough, not cool enough. All these things are to do with false power and prestige, and we feel we’re lacking because we’re told that’s how we’re supposed to behave and think. Well, there are still people in this world who don’t understand that judgement of self or judgement of other ways of life. Native people are sitting there feeling the wind and the wind is equal in all parts of the world, so there’s no need to judge the wind, the trees or the rocks. Those elements aren’t judging. But as soon as those elements give us coolness in the summer heat or warmth in the winter then we start judging them as good or bad. That’s really a lack of equilibrium in a sense.

Our language has, as far as I know, two hundred words for balance, whereas in English as far as I know there are seven. I keep trying to stuff those two hundred words into this little box of seven words and sometimes I’m like, wait a minute, who’s in charge here? That’s what a friend of mine, Martín Prechtel, said in an interview recently, that the Western mind always wants to be in charge of everything because it’s lost control, it doesn’t know how to let go. But I know those who are not Western thinkers and aren’t thinking that they have to be in charge. We’re lying to ourselves, to the animals, and all the elements if we think that we can control and be in charge.

A young Navaho man said to me “yeah, we don’t think too much. We don’t think that we can think our way out of this situation. When we pay attention only to our mind it throws everything else out of balance.” If you’re paying attention to the consciousness of the Earth there’s no need to think, because thinking is merely an abstraction of ego. A tree is not egocentric, it’s there, really living, moving in motion, in balance. When you’re watching this movement of the universe you see that you can’t really control anything. You know no one is in charge.

You have spoken a lot about asking and reciprocity, and I wonder what you think of the concept of service, a central practice of selfless loving kindness in Sufism. Okay, so if we go to the heart of the word “service,” it’s an action. Action is dealt with in the Western world as a binary product—either you’re helping or not helping, and you’re judged on the value of service.

We are usually looking for a benefit in everything we do, because we have a sense that we’re lacking. If we help charity we’ll feel good about ourselves, and we can write it off on taxes. That sounds like we are expecting, like we’re setting forth an insurance policy. With the Native way, you just give because you become instantly healthier—the health of giving without expecting anything back. Being a warrior of service is a one-way energy of giving, because that’s what Mother Earth is doing—giving.

It’s hard to give without benefit. People say, what do I have if I give everything away? It’s always fear based. You don’t have anything in the first place, and generosity is reciprocity—that’s the difference that I have seen in my lifetime.

What are your feelings about the imagination as a place where we can more freely understand the Earth? The Earth has imagined you, has dreamed of you, has created you. Earth used its own self to create you in service, as you would say. We are the living dream of this entity called Mother Earth, but instead of freely accepting that mystery, we are trying to figure out “who I am, what I am.” We send rockets out, and take things apart to find out mechanically who and what “I” am, which makes way for artificial intelligence—another tangent from our natural ability given to us by Mother Earth. Illumination of who we are… it’s a light inside. Scientists have witnessed by electron microscope that when male sperm touches the egg, there’s a flash of light. This light that is within all of us is the imagination that we’re not giving credit to, because we think that we’re the only ones in the imagination of creation. If you watch a bird, they are in their own imagination. They’re creating song, they’re creating flight, they’re creating color.

In the languages of old, there came a cosmology of how to relate to Earth. A spirit lived everywhere and this energy began to speak to all the peoples who came here wanting to learn how to live with Mother Earth.

What is your view on technology, and do you see a way in which we can balance different elements of human society with the needs of the planet we’re living on? Well, you know, what we are doing here is also using technology in a good way to continue the message. I’m not saying technology is bad, it’s how we use it.

I think humans here, in the United States at least, have forgotten how to listen. It’s not a listening nation. It wants to speak all the time, to overrule anybody who’s listening. And it’s not just human beings that we should be listening to. We didn’t really have to really employ the word “science,” or cut things apart to understand life or make things work technically or mechanically. People want to imbue technology and artificial intelligence with life, but it doesn’t know how to feel. It can be compassionate, it can be sympathetic, but it will never know how to feel. That comes from some source that we can’t even begin to name. We’ve distorted all of the technologies that we can to try to give credit to ourselves as creators, to become the god of ourselves.

In the West, they think so highly of themselves that they think they can put technology and spirituality together as if it was one consciousness, because they are not dealing with their own conscience as a priority. The priority is: I don’t want to feel guilty so I only talk about the positive, and if I only talk about the positive that’s already an imbalance because it’s not allowing the negative to come in. This is why it’s difficult for even Native people to speak in Western institutions because they’re looking for a win/win, positive/positive situation. There’s no shadow there, there’s no nighttime to allow things to heal. We need to balance this stuff out.

Technology can only support the spiritual. Technology is not the universe, the spirit is. It’s like we’re trying to rationalize ourselves, trying to insert ourselves into spirituality. I don’t think it’s ever going to work through technology, because it only takes a switch to turn off technology. Someone’s got to control it. Technology leads you into the matrix where they want to own what you say, they want to own what you buy, they want to own how you walk, and how you look, and they’ll teach you the language to do that by getting rid of nature. You will no longer be of a spiritual nature, you’ll be of a technological nature. It involves extraction, isolation, always trying to rationalize why you need to be alone and why the human race is unique and there’s nothing spiritual except our own minds. But why aren’t we saying all life is spiritual? We need to balance technology and spirituality together, balance the rational mind and the intuitive mind.

I find it really interesting what you were saying about positivity and the shadow, and it occurred to me that the emphasis on positive thinking which you see a lot in New Age psychology “just think positively and everything will be fine,” is like a kind of silencing. Following on from what you were saying about the experience of Native peoples in Western institutions, what do you think the role of active resistance is in safeguarding a human culture which is intuitive and balanced? The political nature of spirituality is the highest form of intelligence for many Native people here in the Western hemisphere. To be spiritual and political is not only dealing in the realms of humans. In Native government our decisions are based on Mother Earth, not on financial gains.

During the spiritual movement of events like Standing Rock—and I call that a consciousness movement—we relied on technology. But where did it go? It went right back into the box. The court systems, the governments and corporations stepped right in and made those spiritual people look bad and wrong for resisting energy technology. Government is extractive as far as my experiences is concerned. Extracting people’s minds, even their spirit or energy. Telling you when you have power on voting days, saying “just give us the keys and we’ll give you water, we’ll give you food”—but it was free before, so why is it not now? If we were living the cosmos of Mother Earth, we would see that there is no need for government. Civilization means individuality, to cut people apart, to civilize people and say well, books are education, books will give you intelligence, but that’s not intelligence, that’s not spirituality, because they removed you from nature. The more civilized you are, the more removed from nature you are, the more you act like you’re not from the Earth. And of course that’s an abstraction, to act like you’re from another planet.

The cultures that have been called “primitive” are the ones who are not resisting the greater law of nature—universal law. We’re trying to maintain that balance, as a Native people, to protect it. And I think that’s resilience. We’re standing the storm of technology and the nosedive of Western civilization.

I wanted to ask about storytelling because it’s often through stories, fables and myths that we reflect on our relationship to each other, to ourselves, and the Earth. Stories have this capacity to encompass the spectrum of reality—the shadow side, the positive side. What importance does storytelling have in nurturing spirituality and in the resistance that you just described to a culture which is out of step with nature? In the languages of old, there came a cosmology of how to relate to Earth. A spirit lived everywhere and this energy began to speak to all the peoples who came here wanting to learn how to live with Mother Earth. It gave us form and each of the elements gave us their story and so within our bodies are the stories of our origins: where the rocks came from, how they probably came from someplace else, or how the light or fire came here. When I think about fables (which means “false”) and myth, which is “made up,” it’s misleading—the myths of the “little people”, the Native person, did exist. If you sit around a camp fire, that fire is essential to our learning process. If you stick your finger into the fire you’re going to get a lesson—maybe we should pay attention more to the elements and their stories. Our memories are stored within these elements, and if you’ve forgotten the language of Mother Earth, your story is not going to be long.

English is a young language, and it’s meant to proselytize its way of life. It emerged with Christianity, and it is still evolving. It focuses on progress, on getting something new. Native languages have less explanation, they have a quantum, multi-dimensional view of life. We’re in constant flow, we’re in constant unity; we don’t have to “reconnect” because we are unified.

English excludes because it wants to make individuals out of all of us and [as a result] we don’t have a shared story. Its story doesn’t deal with wholeness at all. It deals with the practicality of rationalizing everything in existence, so that it can exist. Our mindsets have come to destroy and we know that it’s adverse to creating any story that will go into the future. Maybe there will be an ending story, because this will be the end of creation. There will be no more stories because one way of life, one way of thinking believes it knows the answer.

When we go back to the originality of consciousness and the languages that are there, vibrant, speaking every day to us within our body, we can listen to the greater story that the Native people hold here, not because we’re special, but because we’re still conscious of Mother Earth and the creation story. That story is peace. Peace with Earth rather than peace on Earth.

You’ve dedicated a huge part of your work to giving a voice to the Indigenous perspective and other Native peoples in the different communities who are still living in the way you describe a voice. Have you seen a shift in the cultural balance between the story that you represent and the story of individualism? I think one needs to know that the Native story has always continued. Mother Earth has always been here. That’s the original story. She will continue after humans are long gone. We think that humans are needed here, but not in the context of control and domination of the Earth.

We think we’re too good to learn the struggles of Mother Earth. That’s why a lot of the Western world, and even my own people sometimes, forget who they are, and it’s hard to address shame about how we treat the Mother Earth or even our relatives. We forgot the empathy of Mother Earth. And in the long run, we’re sitting here with a bucketload of grief. We forgot how to grieve with Mother Earth

But when the story continues, what is the legacy, what is the story people are going to leave behind? Is it guilt? That’s something that comes out of Christianity and binary thinking because we don’t know how to deal with grief. When people and cultures don’t deal with their grief, they push it onto Native people. They praise themselves and say, “poor Native people.” But when you live amongst Native people they don’t judge in this way, the domination factor doesn’t exist, they observe. They just want to help, to be generous. They have nothing, no material, no bank, but they always want to give. They see Mother Earth at the heart of everything.

We need to look to those who are being resilient, the ones who are really resilient are proud to live with Mother Earth. It’s the ones who are living against Mother Earth who are the ones who are really resisting. They think it’s bad to be in nature, to live in nature, to be with nature, to not have faucets and not have cars, not have electricity, not have technology. They think that’s resisting life, but it’s really not. There are many more other accessible dimensions to gather intelligence and intuition to live, to teach us how to live.

Of course you’re a musician too, and music sometimes has a capacity to cut through whatever story we’re living in and touch the part of us that is in motion. What is your experience of playing and making musical instruments and do you see it as an important part of how we go beyond the dominance of the mind? The flute goes way back in all cultures to the beginning of our human time as we know it. That’s one magical instrument. If we really want to know music we’re going to have to go listen to the birds. That’s where we get our songs from. We have to go listen to the meadow lark, to the eagle, to the bear. We listen to all the animals that we possibly can before they go away, before we forget how to know song, and where it comes from, because we’re definitely not the only ones who can sing.

People say that all music is good and I have to disagree with that—music can be used to control and manipulate, just like language. You can’t play a Native American flute in some deep, dark dungeon of a bar or a pub and watch people yell at each other with loud music, being cool and having intoxicating drinks while they lose their sense of self—you can’t hear Native American music in those places. The three affiliate tribes in North Dakota have a certain ceremony where they sit for ninety days and sing a song to a cedar tree, and after ninety days they learn how to become the tree, and the tree finally begins to sing back to them. The “tree-ing” is not stuck in the time concept of a three-minute interlude of “I begin here and end here and now we have to put another song on to keep us hyped up.” No, you find a consistent vibration with nature. That’s music.

So when I play flute, it’s coming from the wood, the tree. I’m putting wind into the tree. My body and all the makeup of those elements I described earlier in this interview said, “play it this way.”

Beautiful. Thank you so much Tiokasin. It’s been such a pleasure. Is there a last thought you can leave us with? Yeah. I think one thing would just be to learn how to be consistently generous to each other, to the Earth and to yourself without taking too much, even when you don’t have anything else to give.

[/wcm_restrict]

PHOTOS © NANCY GREIFENHAGEN

[wcm_restrict plans="Sufi Journal Digital Edition, Sufi Journal Digital Edition old"]

RETURN TO ISSUE 96 TABLE OF CONTENTS

[/wcm_restrict]

[wcm_nonmember]

To read this article in full, you must Buy Digital Subscription, or log in if you are a subscriber.

[/wcm_nonmember]