The Song Becomes Everything

The Song Becomes Everything

Kanai Das Baul and the Path of Longing

by Surat Lozowick

No fear in singing

Why are you afraid? We’re scattered in a circle, trying to match the melody that Kanai Das Baul sends high into the air, like a bird sent far then called back, sending messages to that which made us, returning with wisdom to share. His voice flies clear, straight, true: melody simple yet beautifully precise.

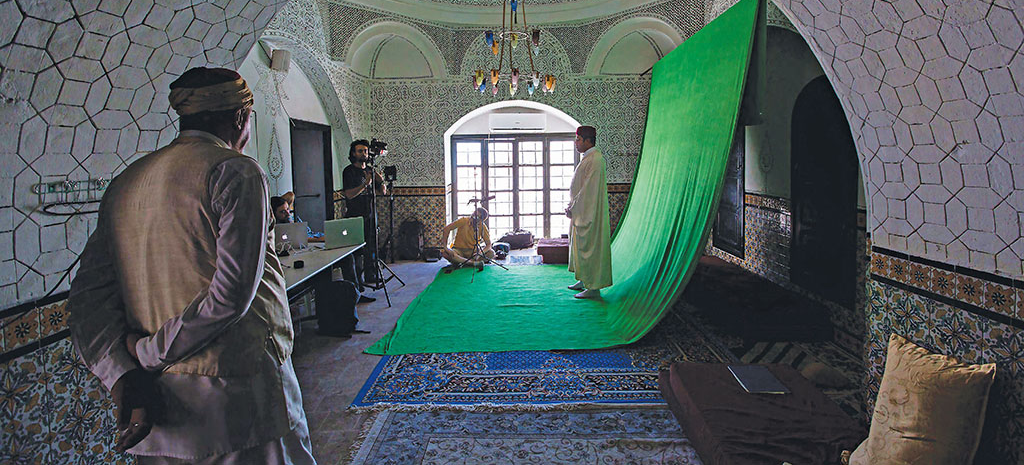

Night descends, darkness and a slight chill coming through open barn walls, cloth ceiling above us breathing with the wind. Kanai Das Baul, “Kanai Da,” sits attentively at the front, lit by LED lights, ektara (a single-stringed drone instrument) in one hand, ankle bracelet in the other.

“Oh Brother, my Beloved Friend,” he sings in Bengali, to Krishna, “when the bird of breath escapes the cage of my body, spreads its wings and flies away”—when I die—“that day, will you be there, will you remember me?”

We respond, but we aren’t singing in unison. Our voices collide and wrestle in the air.

Patiently, undemanding, he sings the song again and again. He doesn’t get frustrated at our pace of learning. He gets bored. (He who at other times sits contentedly as we talk for hours in unknown words, the majority untranslated.) Tonight we’re here to learn, and we’re not paying attention.

“It’ll take time,” Arpita, translating and helping teach the song, says to him on our behalf.

“Of course it’ll take time!” he says in Bengali. “I’ve spent my whole life taking time, and I still have more to learn. But sing together.”

On the third evening, as we flap through another repetition, he stops singing.

“Why are you singing with so much fear? There’s no fear in singing.”

“In the West, everyone’s afraid of being wrong,” I answer, speaking primarily for myself.

“Why are you afraid? There’s no fear,” he says. “Open your voice. Throw the voice as far as it can go.”

We sing again. This time it’s different. “It won’t work when the voice is closed,” says Kanai Da. “If you open your voice, you’ll feel good inside, and it’ll sound good too.” We all feel it. The air, our voices thrown unreservedly into it, is more full.

Still, we are just beginning. Now, with less fear in our voices: “Sing louder!”

Wherever my ektara takes me, that is my work

Kanai Da is a Baul, a God-loving, God-singing, God-breathing minstrel who lives in Tarapith, Bengal, India, where he sings to Divine Mother Tara—singing, as his contemporary and friend Parvathy Baul says, with the Divine Mother’s own voice.

Today, alongside her and two traveling companions, he is in lumber country in the Okanagan, British Columbia, Canada, sleeping in a canvas tent under pine trees by a drought-dry stream on the Kripa Mandir ashram of healer turned Western Baul teacher Lalitha. Lalitha has gathered Bauls from India and North America to her farmland sanctuary for an exchange of teachings and songs between the two traditions, Bauls of Bengal and Western Bauls. The Western Baul tradition was founded in the United States by Lee Lozowick (born 1943, died 2010), ancient seeds in modern earth, and became associated with the Bauls of Bengal through a resonance of practices.

In bright orange robes, Kanai Da squats in the dry grass, smoking a bidi, with an empty sunflower butter jar beside him for ashes. As long as he has hot black tea, thick with sugar, and bidis, he is content: at home on the wood porch of his tent, taking in the morning sun, as he is at home on the funeral steps of Tarapith, with his friends the beggars, the tantrikas, the aghoris, the poor, the mad, the dead.

The cremation ground (smashan) of Tarapith is his “office,” he says. “I go to my office at 8 am, go home for lunch at 1 pm, return to the office at 5 pm.” His work: singing to the Divine Mother.

Sitting in the grass outside his tent one evening, I ask, “You don’t miss the office?”

“Na. Here is office. Wherever I go, that is my office. Next the airport. I come, I go, everything is the same. Wherever my ektara takes me, that is my work.”

Filled with compassion

True Bauls are hard to find, says Kanai Da. With “modern” Bauls, “their minds are functioning.” The Baul mind was once empty of thought and filled with compassion. Now, he says, there’s too much intellect.

Yet from Kanai Da, compassion shines like one lit by the golden rays of the morning sun. He carries calm rootedness in his body, roots reaching up to heaven, to bloom beauty and heart onto earth. His sixty-three years show on his wrinkled hands and his vast grey-black beard, but he lives in his own body a relationship outside of time: the eternal devotion of Lover and Beloved.

It’s not the details of his life that imprint in me an impression of who he is—it’s his voice, like earth, solid yet wildly alive; the way he claps his hands when he sings, steady, soft, deliberate; the way his hands are always active when not holding an instrument or clapping, running over each other like a farmer washing his hands after a day in the fields, a constant movement which yet leaves the calmness emanating from him untouched; the still focused attention expressed on his face; his hand pulling through his beard; his wrinkle-eyed, open-mouthed laugh.

The wisdom of one such as Kanai Da is a lived wisdom and a living wisdom. Between the countless songs and poems he carries is the simple space for life to be lived, naturally, spontaneously, fully, beautifully.

His eyes are blind, but when he squats in the grass taking in the polished-bronze light of dawn, or sits on the couch still and quiet as we gab over dinner, one suspects that he sees something most of our hearts are closed to.

In his heart, I sense, he is with his Beloved. It is her we hear him calling, tenderly, powerfully, joyfully, when he sings. In silence he is with her too. His song to her does not stop when his voice does, and the silence they share is not interrupted when it starts.

Still sitting with the Goddess

“I’ve been through a lot of hardship,” he says, “That’s why the Divine Mother has given so much happiness inside.”

Parvathy asked him once if he has pain, she tells us, and he answered:

“I started my journey. The Goddess came into my life, everyone came, and then everyone left. I’m still sitting with the Goddess.”

His guru said Kanai Da would meet many people. He said, “All the meetings will come but also leave. It’s a cycle. They will leave today but more will come tomorrow.” Thus he must not be attached. He found these words to be true. One by one his family left—some to death, others to marriage. Now, free from familial duties, he wanders around, he says, enjoying his life, accepting what is given, accepting what is taken.

One of his gurus, Gyananondo Goshai, told him not to go begging on buses and trains, as some Bauls do. “Stay in one place,” he said, “If you need anything it will come to you.” So, he stays in the “office” in Tarapith. Everything he needs does come to him, he says. He lives in a mud house, the last in the neighborhood, surrounded by modern two-story buildings. Many people help take care of him, Parvathy tells us, from other musicians to the flower sellers at the temple. In 2002, he met Canadians in India, and decided he wanted to go to Canada. Now, on Lalitha’s invitation, here he is. “My wish has been fulfilled,” he says. “Divine Mother made it so.”

Singing to survive

When Kanai Da was ten years old, his father died falling off a ladder. He, blind since a young age, was left to care for his mother and sister.

There were many Baul practitioners in the village, and they would sing every night. He would listen. He might remember only four or five lines, but he would repeat them throughout the day. People would sometimes give him money, food, or rice.

“He had no instrument,” says Parvathy, so “he took two stones and played them against each other.”

When he didn’t beg enough money to feed his family by singing in the streets, he would go to community houses. He would say openly that he couldn’t earn enough that day, and they would give him cooked food to take home. He would go to as many houses as he needed to feed his family.

He used to play in the temple in Tarapith, 9 km from his village, and was attracted by the funeral ground. As a teenager he would sometimes spend the night there.

I ask him how old he was when he began singing in the smashan, and he begins counting the years backwards to find out. But the number doesn’t mean anything to him, so he’s not sure. He says he’s been sitting there full time for at least 37 years. Parvathy thinks it’s more. (He’s 63, and has been going there since being a teenager.)

His colleagues in the funeral ground “office” used to remember how long he’d been going, he says, but now they’re all dead, so he has no one to ask. He says this matter-of-factly, with humor.

“We all want to tie and measure everything, counting days,” comments Parvathy, “for him it’s the opposite. He’s just being who he is.”

In his every word and gesture, Kanai Da sends a message: what matters is not the years of the past, but today. Today, like almost every day, he will sing the songs he’s learned, many which remind us we will die, and that only love is eternal, love for Krishna, the Dark Moon, the ungraspable eternal lover trysted in longing. Today, and every day, he shows up to his office and does his work, as he will until the “noose of the God of death,” as one song says, tightens around his neck; and then, “Dark Moon, I will know what kind of friend you are.”

“You can have beautiful language,” she explains, “but you must start with the alphabet.”

The song becomes everything

He worked hard to learn each song, he tells us. He cannot read or write, and not all his teachers were patient. Some would run away, or reject him. But he was resilient. Every song is precious, he says. “The song becomes everything. Your house, your friends, your parents, your companion, everything.”

When Kanai Da was young, his gurus would call him with compassion. “Ok, this old man is calling me, I’ll keep him company,” he would think. They would teach him wisdom and repeat poetry for him to memorize.

As he tells of his meetings with teachers, he begins reciting one of the first poems he learned. He has to finish, uninterrupted, before translation can continue, like he’s holding a scarf that cannot be taken from the weaver’s hands until the final knot is tied. It is a test for his memory. When he finishes, he is relieved. He can relax. The poem is in its proper place, complete, unbroken. Translation can continue.

He tells of Pagol Bijoy, an aghori practitioner and poet who would compose spontaneous poetry, many poems which now are preserved only in the memory of Kanai Da. “Pagol” means mad. Pagol Bijoy would speak poetry, and his assistant Horidash would write it down, then put it to music.

Pagol Bijoy was singing in the smashan in Tarapith and said he would write a song for Kanai Da. Kanai Da told him he would not remember, because his mind could not sit still and learn poetry. His mind wanted to go to the tea shop, then have a samosa. The poet said no problem. He would repeat the song 40 times if necessary.

He did repeat it nearly 40 times, says Kanai Da. And Kanai Da really wanted to go have tea, but he stayed until he’d learned the song. The poet told him to put the words to a melody. When he sang it, the poet went into ecstatic bhava, crying, and hugged him. After that, Kanai Da would visit him once a day, every day. The poet would have tears in his eyes when he arrived. He used to cry so much with love for Kanai Da that Kanai would have to leave, just so the poet could stop crying. He would speak poetry and Kanai Da would compose a melody. The poet used to scold Horidash for not composing like Kanai Da.

Song by song, he learned. Yet even with decades of songs memorized and lived, he says he is sad he can never learn all the songs there are to learn.

A daily practice, morning to night

In outer expressions of Baul culture one can see madness, spontaneity and iconoclasm, but the core of their way of life is sadhana: disciplined, committed, daily practice, of both music and esoteric methods of transformation.

“One thing I want to remind everyone, and myself also,” says Parvathy, “is that it’s a strict discipline. You must practice as a musician, and then you can transcend. But first you must practice technically.”

“You can have beautiful language,” she explains, “but you must start with the alphabet. As a child you must learn to read and write. Even speaking, you must know where to put the words. On a Baul ashram, a child born there learns the songs very naturally, almost like breathing. But when you come from a different perspective, you see that there are many steps. Even how you stand, how you breathe. It’s a daily practice, morning to night. It’s not like you practice meditation for seven hours and then you’re done. You have to practice every day.”

For one who grows up surrounded by Baul music and culture, is there an age when they could be considered a Baul? someone asks.

“Am I a Baul?” Kanai Da asks in response. “There is always more to learn, there is no end. There are infinite songs to learn. Even I am still learning to be a Baul.”

Not all Baul practitioners are performers. Some live the teaching in other ways. Yet an intensity of focus on sadhana remains core. “The music is a vehicle,” says Parvathy. “Some people sit in front of a fire; we play ektara and sing.”

You cannot run out of this gold

Parvathy emphasizes the necessity of working with a guru, a living teacher, on the Baul path. “The guru is neither man nor woman,” Parvathy says. Yet “When the guru takes a human form, he or she takes on all the human functions.” We have to see beyond this. “What is the essence the guru is carrying? That is what we will have to look for.” From how we look, our view will change, she says. “When we see the divine in him, we can start to see the divine in everyone. Even a dog. We can see a dog as our guru. See compassion in it.”

“Guru yoga is very difficult,” says Kanai Da, “so we need guru kripa, guru’s grace, to be in guru yoga. Guru kripa is a state of lightness. You cook and serve, but you don’t touch the pot, and you should not be hungry. The grace of the guru is to be completely free, even free of wanting the fruit of sadhana, of wanting to be realized. Not attached to getting something, believing if we follow obediently we’ll get something. Not wanting, just being, that’s the grace.”

Kanai Da and Parvathy attribute everything given in their lives to the grace of their gurus. They are instruments; the guru is the conductor and the orchestra.

“We must be slaves, just workers on the path,” says Kanai Da. “He is my employer, and there’s no retirement.” He laughs.

“Your guru is you,” says Parvathy. “But not in the sense of ‘I am my guru.’ The human who is sitting in front of you in the form of the guru is you.”

“If you search, you will never find the guru,” says Kanai Da. “Because he is there, he’s present with you. Searching is outside. Be with the guru, don’t search for the guru.”

“He fills your life with practice,” says Parvathy, “so there’s no room for anything else.” She continues, “my sadhana is one-string. I cannot think of anything else. I am filled with my guru’s ornament. Gold.”

“You cannot run out of this gold,” says Kanai Da. “You give it away and you have more.”

“Everything is impermanent,” says Parvathy, “except that ‘I,’ which we call love, to give it a word. Even words are impermanent. Only the essential ‘I’ exists.

The practice of the heart

“In Baul, it’s the practice of the heart,” says Lalitha. A quintessential mood of love for Bauls is that of longing, the heart both broken and full.

Jim, a Baul practitioner from the United States and Lalitha’s husband, illustrates this with a poem written by Lee, the Western Baul teacher, to his own guru Yogi Ramsuratkumar. It ends,

“The Old Man, ageless, eternal / has cracked his son’s heart

in order to heal it. / Who would guess that despair

mixed with Praise and Worship / would be the sacred balm

of Union and Oneness?”

Jim comments, “Without the polarity of both despair and sweet heartbrokenness—heartbrokenness which is expressed as praise and worship—then neither would exist. It’s not like we can leave despair behind.”

As Kanai Da waits for translation, he begins commenting in Bengali to Parvathy.

“What did he say?” asks Jim.

Parvathy smiles. “He just said exactly what you said.”

“The words are nectar because they come from the guru,” continues Kanai Da in Bengali. “After seeing, thinking, experiencing, realizing, experimenting . . . only then they write.”

A surprise that you’re alive

After singing one afternoon Kanai Da speaks on death. His words, as always, leap from poetry, inspiration, humor, his own experience of life, and all that is learned by repeating thousands of songs until they become a part of his body, as intimate as his own breath.

“Death can come anytime, anywhere,” he says. “Death doesn’t have any rules. Death is present. Death doesn’t listen to anyone.”

“I’m here, I’m talking, and suddenly, I have a heart attack, I’m dead. I’m here at this moment, but death can take me, so what does it mean, staying here? And after, I’m not here.”

“Usually we refuse to think we will die. We always think we will never die. But if we know in our hearts that we will die, know that that day will come, then we live longer, because we don’t waste any moment.”

“Life is a gift. It is a surprise that you’re alive. Every morning you wake up and it’s a surprise—the gift of being alive.”

“If we could spend every moment of our life in our sadhana, moving toward Brahman [pure consciousness, supreme reality], our lives would be even fuller.”

“One who knows this truth and who is living with the divine every day can decide between life and death, even the time of death [for a great yogi]. Then death is not a surprise. For a sadhaka, death is not an accident. For most people it’s an accident.”

When he stops speaking, the reality of death sits with us in the silence.

Lalitha adds, “If you’re aware of your death, every day, even if you don’t know ‘I’ll die in ten minutes,’ you can be prepared.”

Parvathy says her guru Sanatan Das Baul began talking about his death from almost when she met him, over two decades ago. Before he died in 2016, he spent time visiting the samadhis (tombs) of other great yogis, deciding what time of year he wanted to die. For many reasons, including the seasons, astrology, and the deaths of other yogis, he chose February. He died February 28, 2016.

What was Sanatan Das doing to prepare for his death throughout his life?

“He watched his breath 24 hours a day,” says Parvathy.

Only the essential ‘I’ exists

“Everything is impermanent,” says Parvathy, “except that ‘I’, which we call love, to give it a word. Even words are impermanent. Only the essential ‘I’ exists. This observer that even as a child is the same, that has no age. This is love, which we cannot hold, but we can sense.”

“All humans are humans,” says Kanai Da, “American human, Canadian human, Indian human. The essential ‘I’ is the same. This has no culture. The form might be different, but the truth is the same.”

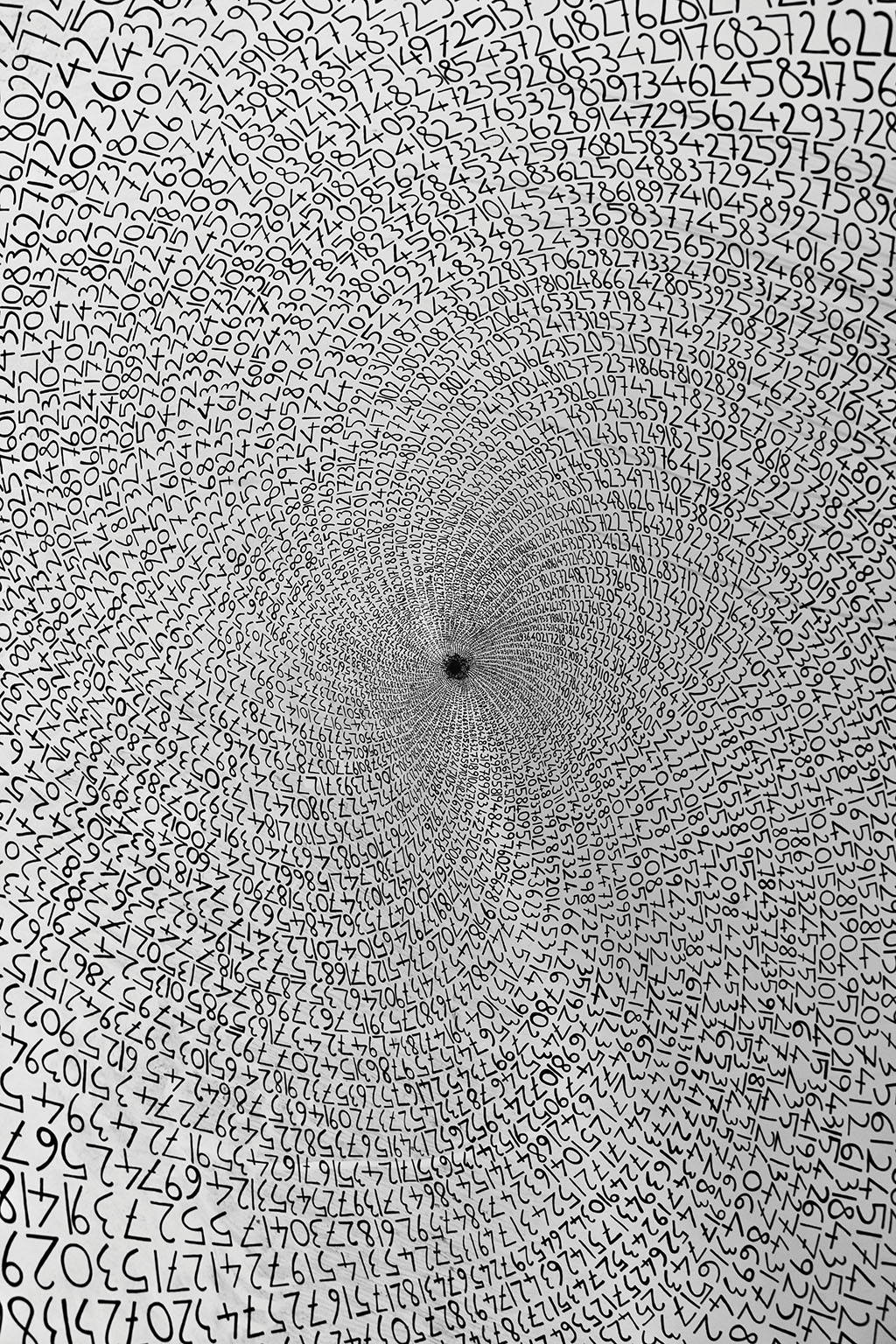

ARTWORK © SEKHAR ROY

PHOTO © PAWEL BIENKOWSKI PHOTOS / ALAMY.COM

[wcm_restrict plans="Sufi Journal Digital Edition, Sufi Journal Digital Edition old"]

RETURN TO ISSUE 96 TABLE OF CONTENTS

[/wcm_restrict]

[wcm_nonmember]

To read this article in full, you must Buy Digital Subscription, or log in if you are a subscriber.

[/wcm_nonmember]