THE ART OF FIGURAL CALLIGRAPHY

THE ART OF FIGURAL CALLIGRAPHY

by Jila Peacock

I was born in Tehran to an English mother and Iranian father, and, although English was my mother tongue, my first written language was Persian, which I studied from the age of seven at my Iranian primary school. I remember being introduced at that time to snippets of Ferdousi in my first textbooks, to Sa‘di, my father’s favorite poet, and Edward Fitzgerald’s translations of Khayyam, which my mother would always recite by heart. My introduction to Hafiz came much later in life.After reading the 81 poems of the Dao de Jing on a working visit to China as a young doctor in 1977, I became interested in the ideas in these teachings of “emptiness” and “oneness of all things.” Naturally I found myself seeking out similar universal ideas in Persian mystical poetry, and more than any other poet, reading the ghazals of Hafiz of Shiraz became my quest. At a family gathering after my father’s funeral, I asked my Iranian cousin Behnoosh to do fālgīrī for us by selecting a poem from Hafiz’ collected works, or Divān. fālgīrī, meaning fortune-telling or divination, here specifically refers to divining by means of the poetry of Hafiz, which is the most popular form of divination in Persian culture.

The poem that was “given,” number 172, happened to be a well known favorite and ten years later became the poem from which I made the image I call the “Perfumed Deer.”

What is astonishing about Hafiz’ work is that it can be interpreted in so many different ways. This is because his creative use of symbol and metaphor, internal rhyme and repetition, makes the meaning metamorphose with each new reading, giving a sense of the poem hovering, just beyond the reach of reason.

As an artist, the language I find most natural is that of the image, and Hafiz’ poems brim over with images. A pageant of planets and stars, kings and conquerors, wise men and fools are conjured in his writings. In particular, he plays metaphorically with flowers and trees of every form, and a virtual arc of animals dance through his lines, painting layers of metaphysical ideas which cannot be communicated through words alone.

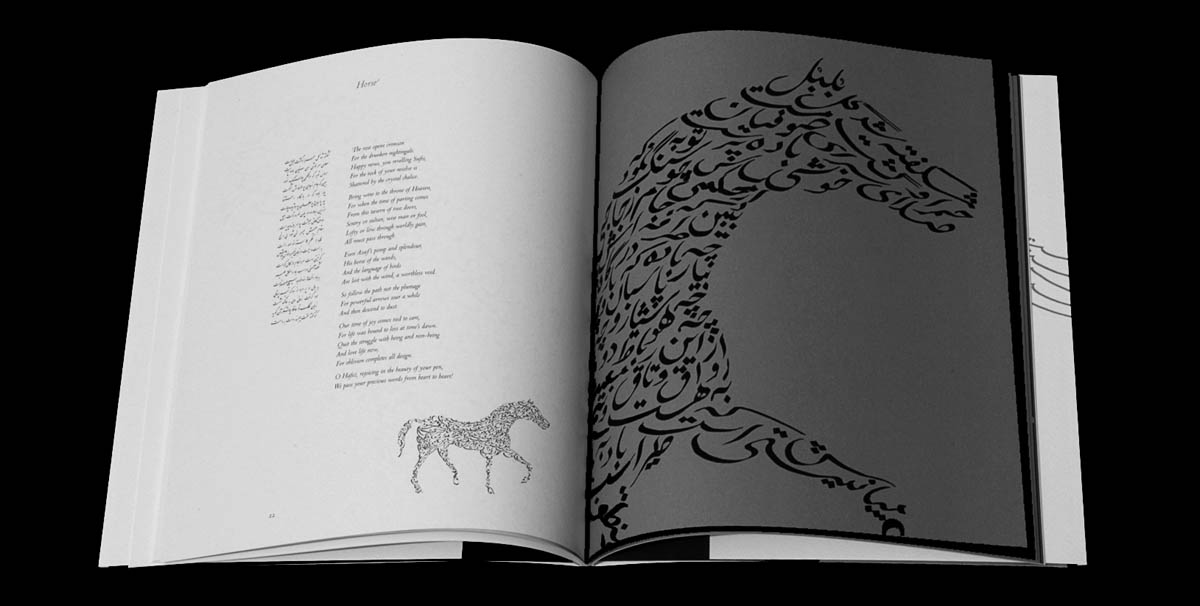

Since the 15th century artists have illustrated handwritten books of Hafiz’ Divān with miniature paintings of animals and flowers. When I first started to read and memorize Hafiz, guided by my friend Dr. Nazanin Mousavi in Glasgow in 2001, I had no idea what might result. What thrilled me at first was how easily I remembered my long neglected Persian script. As I memorized more poems, I found myself responding in particular to those in which Hafiz had incorporated images of animals as poetic metaphors, the first being the parrot in poem 4, then the horse in poem 20 followed by the fish in poem 144 and so on.

There is a long and distinguished tradition in Islamic art of making images out of words, or figural calligraphy. It occurred to me to use this device to incorporate whole poems by Hafiz into the silhouette of an image. Working tentatively at first and later with growing confidence, I designed the words of the poems into ten animal shapes, refining and sharpening each image until I was satisfied with the result. Now I had a collection of calligraphic animal images which were asking to be made into a book. Working at the Glasgow Print Studio over the next two years, I produced colorful silk-screen prints of these images onto fine Japanese paper and the first hand-made Artist’s Book was ready in August 2004.

The interest and enthusiasm with which this book has been received by friends and fellow artists, has led to an astonishing outpouring of creative activity. New musical settings by Ostad Anoosh Jahanshahi in Tehran and composer Sally Beamish in Scotland convey the brilliant rhythms and complex musicality of the original Persian poems. An award-winning publication by Sylph Editions has made the original book available to a much larger readership. A remarkable animation film The Tongue of the Hidden made by David Alexander Anderson, has been broadcast internationally and has gained a BAFTA nomination. Finally, there is to be a commission from a major dance company for a ballet of the shape poems. Hafiz’ poetry has triumphed beyond all expectation.

The predominant subject for all Hafiz’ poems is love, and thinking about these poems over the past decade has meant that Hafiz himself has become a form of invisible friend for me, as he has for so many of his readers. At a time when bridging human understanding between East and West is so important, it is the poetry of his thoughts which lights our way across.

Jila Peacock

Glasgow

Norouz 1390

Visit the Store to Subscribe or Buy the Current Issue and Back Issues