Diffracting Rumi

on Becoming Human

By Annouchka Bayley

I died as a mineral and became a plant,

I died as plant and became an animal,

I died as animal and became Man.

Why should I fear? When was I less by dying?

Yet once more I shall die as Man, to soar

With angels blest; but even from angelhood

I must pass on: all except God doth perish.

When I have sacrificed my angel-soul,

I shall become what no mind e’er conceived.

Oh, let me not exist! for Non-existence

Proclaims in organ tones, To Him we shall return.

—Jalaluddin Rumi

We have never been fully human. This is the contention of some of the authors who work with post humanisms. Every time I’ve mentioned the word “posthumanism” outside (and even sometimes within) the academy, I’ve been met with variations on a theme of incredulity. “What do you mean posthuman?” Then laughter. This is a state of affairs that is both encouraging and discouraging. Discouraging because it suggests that a fundamental belief about “our” humanism is that we have actually achieved it. Or that we’ve always been there—at least since the Vitruvian Man burst out in all his glory in the Italian Renaissance courtesy of Da Vinci.

Diffraction refers to physical phenomena, processes like light diffracting through a prism on a journey of ontology as it explodes into an array of colours…

[wcm_restrict plans="Sufi Journal Digital Edition, Sufi Journal Digital Edition old"]

But in truth, perhaps we’ve never actually been fully human, and this is the encouraging part, for “what do you mean posthuman?” is also a question that has sometimes been asked in the context of a disbelief in the idea that we were ever human in the first place. Thus, the incredulity emerges at a different segment, a different cut, along this line of questioning: how could “we” be post-something when we were never initially there in the first place? This has usually in my experience been accompanied by an exasperated sigh. Perhaps in other words/glances/nonverbal modes the question has become: why are you being so insanely impatient?

But it is not impatience that drives me, amongst others, to fashion a prism through which to try to glimpse notions of the human and becoming-human. Today, as I sit at my round desk in unreasonably hot (climatically transitory?) weather, provoked by the editor of this journal to write something, I return to something that has always-already been there in my history—right down to level of DNA. And it’s something that as an academic, a writer and a performer, I must and shall bear witness to. Learning Rumi by heart is my heritage, a tradition in my family and from my childhood, and the world that surrounded us: the recitations on the verandas, the balconies, the bedrooms and living rooms, the gardens, streets and khaniqahs that shaped my early and middle experiences of being (towards) human.

So this essay—this piece of storytelling in service of learning to “live and die together well in a thick present” (to reference the writings and projects of Donna Haraway) is not so much a reflection upon Rumi, but a diffraction of one particular poem read through the body and life of a human (in process). But not so fast! First, what on earth is diffraction? Diffraction refers to physical phenomena, processes like light diffracting through a prism on a journey of ontology as it explodes into an array of colors; or of waves that diffract in a pond, rippling over and above and within each other to form a new and temporary watery surface. Such intensities are not about reflection, they do not assume that one unit is separate and another unit is separate and they meet to form a third, or reflect the originary nature of each other (as when you look in a mirror and say “wow, I look so…” or post a selfie and say “well this is so me right now…” Neither are true—they are merely representations of “me”—and often severely filtered at that, as anyone under the age of 35 who has received a selfie will know, or anyone who has children under the age of 35 will know!) Rather in diffraction, these units of being find they are not inherently separate “units” at all but are eternally existing from within each other, momentarily creating new and various forms in the metaphoric and material “garden” that is the manifest universe.

Diffraction 1: Representations. I realize that mirror-like representations are a farce. Why? How? Because sitting with my parents as a child, at the foot of Aga Joon Nurbakhsh, I see something happening. My optical nerves pulse and vibrate and encounter this Other person—Other self engaged in the pursuit of not-self—who is clearly mirroring both my parents in the same moment. He changes states as rapidly and quickly as a pond diffracts into waves on a windy day. I giggle internally (well, what can I say, despite the continual misapprehensions, I am in fact extremely shy) and watch him endlessly and playfully reflect she and he who stares into him. Is it a reflection? Or is it a diffraction? After all, he is of course inimitably him—his voice, his body shape, his own seeing eye. How can one ever engage in reflection? Reflection is too static, too stuck, too dependant on a universe that stays still. Rather diffract! Show the difference differing. Watch the endless encounters buzz and hum with variation. What states might diffract into other states? Read from a position of fana or baqa, would Rumi’s stories not tell something entirely other?

In other words, diffracting something, or using diffraction as a method of exploration and inquiry allows the inquiry to come from a position of seeing the world as a complex, entangled ontology—to see Being as not built up from a number of separate units, but as a entangled flow of phenomena, a surface of intensities, which in Sufism might tug at something within scholars and practitioners’ familiarity with the concept of the Unity of Being. Not at all the same, but not entirely different either, a concept itself that diffracts its own existence here on the page in this set of contextual mark(er)s.

So, to diffract this segment of Rumi (perhaps himself a diffraction of Shams, of Konya, of Persia, of the flow of time and space and matter we call “history”) through posthumanisms, through myself today at this moment, through the context of “would you like to write something for the journal…?” means here to thicken the present with diffractive storytelling. And the story right now is of Rumi journeying from one state to another in his poem. What he points to here is ostensibly a kind of teleology. He talks of evolution, of a history that has lead from the halcyon days of hanging out in primeval soup, to becoming something unfathomable and more-than-human. But is Rumi just talking about evolution in some kind of Darwinian daydream/nightmare where “we” humans move on to some kind of next stage of evolution (indeed there are groups that affirm that becoming-robot is the fulfilment of the Bible—but here I digress into what are, for me, shady and uncomfortable waters…)? Not in this diffraction. Because whilst Rumi may be referring to the process of evolution, in his inimitable style, he is perhaps also talking about a teleology of states and stations along the way to becoming human in Sufic terms.

As I sat at the side of teachers, mentors, mystics and cynics with a perhaps manic curiosity, (apparently I should have been playing with dolls, sorry Grandad) I heard many stories of what it might take to become human in these terms. It would take practice. It would take suffering. It would take dying to selves and self in the sense of “die before you die”—a sentiment that repeats and (re)emerges in mystical literatures across a range of cultures. It would take listening to wise old men. It would take not listening to wise old men. It would take living in the world and not living in the world. It would take getting married and not getting married. It would take having children and not having children. It would take embracing poverty and not being impoverished. It would take learning and unlearning everything you learned. In short: it would take everything (in both senses of the phrase).

Thus, the only way forwards (and backwards, in the sense of tracing the diffraction of personal history) was to embrace the idea that these things—these binaries of having and not having, doing and not doing, being and not being—were all eternally entangled. They were all existing as vital and vibrant parts of each other. And not just as concepts, but at the material level of flesh itself. These concepts were all living as part of my flesh and my experience of being alive on this planet. Much like Rumi’s poem and how I might diffract myself through it (and vice versa), all these knowledges, all these states were co-existing in one and as one. What “one”? Well, in one present-moment slice of identity, in an experience self continually diffracting into uncountable scores of phenomena. Or, to invoke the scholar Karen Barad, perhaps momentarily into a marked body—here, mine.

Diffraction 2: “You’re a tiger.” “No, I’m not.” “Yes, you are.” “No, I’m not.” And so on and so on. I remember thinking in this instant that I wish I were, but the truth (of this diffraction) is far weirder. I’m absolutely a crocus. Now I remember walking into university. I had by chance, managed to secure a place engaging in the academic study of Sufism (amongst other great traditions). We’d had a lecture on Rumi’s poem during our Mysticism in the Great Traditions course (one might indeed pick the title apart, but nonetheless, there I was, less than twenty and very excited.) Later, I went to my dear friend and teacher’s door to ask “What am I? What animal am I?” It was a trick question, to my mind, as I felt about as animal as a block of wood. “Ha!” is the response. “There’s nothing animal about you. But I’ve never seen a vegetable with so much presence.” I breathe the biggest sigh of calm—I’ve been seen but not reflected. I’ve been diffracted in contact with another. On recollection, perhaps it was nothing but a simple farmyard joke. But how I love this memory, that over time helps me to diffract myself. A further twenty years on, I find myself dreaming of crocuses. How beautiful that they grow in often inhospitable weathers. I imagine tigers trampling them underfoot. What is the power of the crocus-human, this particular and strange diffraction (like all others) that moves about on the planet, getting jobs, loving, eating, dancing, crying and wishing? Not much. But simply and only that we grow back. We know that we will grow back in endless diffractions, on endless fields and hope to be picked and given to a lover for a moment of joy.

But Rumi’s poem does something further than offer a metaphoric manual on becoming (and importantly also not becoming) one’s own diffraction of self via dying to different states and realities. Whilst situating these states within the material world (the world of rocks, veggies, animals, humans before the weird and wonderful, speculative world of angels and beyond) he also suggests that these states of being are temporary—that we are always-already dying to self, materialities and concepts: “I must pass on”… And perhaps this is where a brief investigation of the word “transcendence” might come in, both in terms of the poem and its diffraction here.

Transcendence is a word that troubles me. I became uncomfortable with it after a time when I felt its most prevalent diffraction was as a way to deny the body, materiality and to enforce an “us” and “them” that felt akin to the way Enlightenment readings rendered some people (usually non-white, often female) less civilized and more savage, less able to attain to the sacred than others. Thus, I felt that the word itself often carried a colonial baggage that filled its utterance with a whole host of angry ghosts whose voices had been stoppered up and silenced in the wake of innumerable colonial violences. However there are other diffractions to be included…

In English, the prefix “trans-” is applied to suggest something of slippage, of non-binary experiences and contexts. We trans-it from one place to another, existing temporally and spatially in between. We trans-form our homes, our spaces, our relationships, our lives. We trans-late from one language to another, crossing divides in the same moment that we invent them (for as every writer and reader knows, we never truly “capture” the meaning and form when we translate —why should we?—but invent something hopefully strong and beautiful). Thus, whilst to transcend something might suggest that it was originally fixed and we went beyond it, in this reading, we can do something different. All these trans’s are indicative of unfixed and constantly moving realities that go on to make up our simple everyday. Rather than being fixed and transcending out and beyond in order to arrive at another fixed, often disembodied point, transcending might also point to moving along to another state of engagement along an entanglement. Perhaps no experience is ever fully un-entangled from others. Not even the most simple and taken for granted one: being human.

Going further, as Rumi takes us on this journey, we also come to enter into a conceptual place that is simultaneously outside of conception. Perhaps there’s nothing a mystical writer likes more than the stylistic introduction of a paradox! In the context of Rumi’s religious and cultural tradition, and more specifically in relation to the end of his poem quoted here, outside of conception means into the state of returning to Allah—or that which is outside of human experience, and yet paradoxically in the literature of Islamic mysticisms, is closer to you than your jugular vein. Thus, there is something in diffracting literatures and writings in this context again that invokes the entanglement of binaries, of dualities, of separate selves, and othernesses. From the position of being-in-entanglement, these paradoxes of the Sufi kind perhaps become practiced as part of the course of living and dying, part of the everyday, part of the self and the marks we make. They become embodied and alive, a continually diffracted treasure that forces one to go beyond the reasoning mind and its endless, chattering attempt to fix realities. They become part of the journey and the endless work of “becoming human.”

Bearing witness to my own heritage through this brief diffraction of reading and reciting Rumi from my early life conjures up my own experience of making and unmaking marks. Of entangling through culture, through practice, through DNA with the vast heritage of Sufism to a moment of living with Rumi and his journey of states through recitation. Of living and dying together with friends, with books, with thoughts, with messy politics, with messy cultural traditions, with clear and unclear conflicts, with jobs, with mysticisms, with parents and families and pets, with displacements and revolutions, the thrills and sorrows of being always in-between. Of bearing witness in my own small, tiny way to becoming, always becoming, human.

[/wcm_restrict]

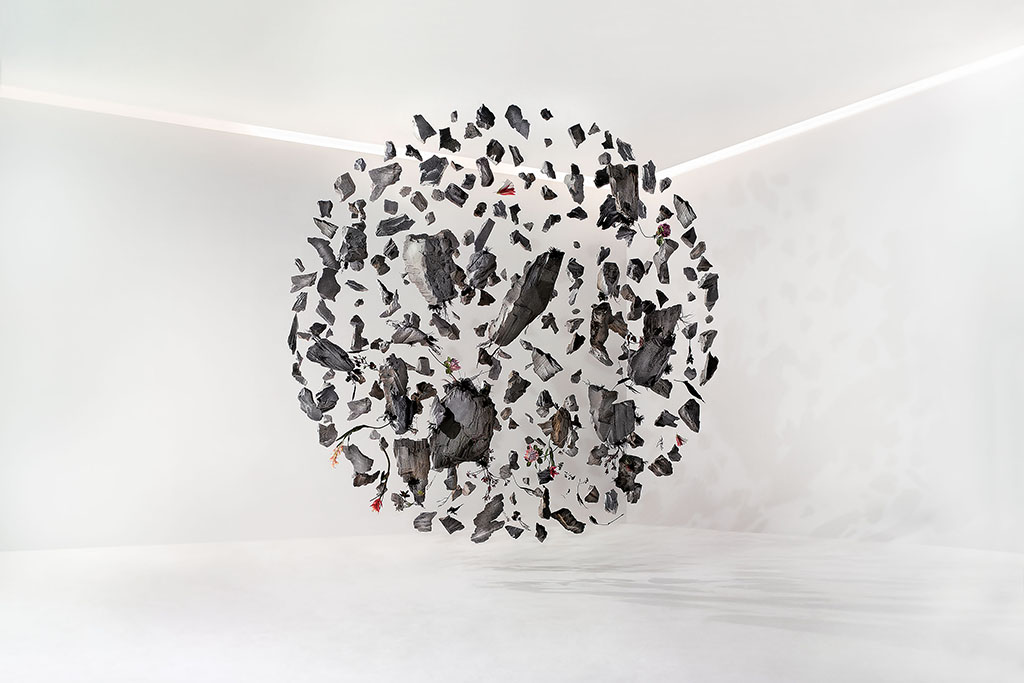

PHOTO & INSTALLATION © LYNDSAY MILNE MCLEOD AND LUKE KIRWAN

RETURN TO ISSUE 96 TABLE OF CONTENTS

[/wcm_restrict] [wcm_nonmember]

To read this article in full, you must Buy Digital Subscription, or log in if you are a subscriber.

[/wcm_nonmember]