The Art of Dream Inquiry

The Art of Dream Inquiry

Cultivating Seeds of Light

By MARY LANE POTTER

A dream is a letter from the Beloved,

written to you alone. Read it.

A dream is a gift from the Absolute Mystery,

fashioned for you only. Open it.

A dream is a seed of Light sown in your unique being.

Cultivate it so it bears fruit.

Not all mystics are granted visions. Very few can, like Ibn ‘Arabī, train the active power of the imagination to create manifestations of Reality on other planes of existence. Even fewer receive prophetic or “true” dreams, dreams inspired directly by God. But all travelers, all those journeying toward the One, dream. And “a dream is one-sixtieth part of prophecy,” say the ancient rabbis; “a pious dream is the forty-sixth part of prophecy,” says Salih Muslim. Though our dreams may not be “true” dreams, there is true knowing in our dreams and, with practice, we can discover the truth hidden there for us. Just as the practices of retreat, dhikr, meditation, contemplation, music, breathing, and visualization loosen the ties to ordinary consciousness, so too may the spiritual practice of dream inquiry. “A natural state of sleep is like a profound concentration, like deep meditation,” Hazrat Inayat Khan teaches, “and that is why everything that comes as a dream has a meaning.” (Healing, 213) Learning how to receive that meaning is part of the path of a Sufi, which is not to converse with fairies and spirits, see colors and visions, but “to connect with one’s deepest, inner self, as if one were blowing on one’s inner spark.” (Inner Life 91) The art of dream inquiry can help us blow on that spark.

[wcm_restrict plans="Sufi Journal Digital Edition, Sufi Journal Digital Edition old"]

A farmer went out to sow his seed. As he was scattering the seed, some fell along the path; it was trampled on, and the birds ate it up. (Parable of the Sower, Luke 8:5) For a traveler, everything is pregnant with revelation. I was a hidden treasure that loved to be known and therefore I created the Universe as a means of knowing myself. (hadith qudsi) Why, then, do so many of us neglect or dismiss dreams? A cultural leaning toward a materialist view leads some to disregard dreams as random firings in the brain signifying nothing. Others assume dreams are simply projections of desires or eruptions from the unconscious. Still others consider dreams mere fantasies, that is, not real, and therefore misleading or distracting. And some regard dreaming with suspicion because of its association with being asleep, not being awake to the One.

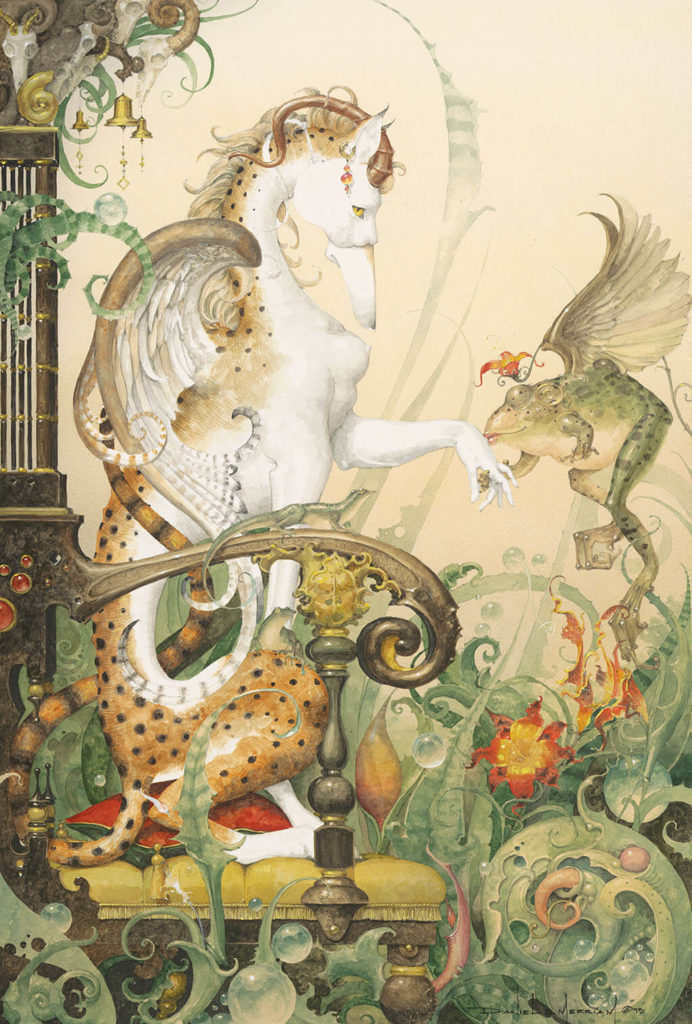

A more welcoming approach to dreams suffuses Sufi tradition. For those who seek the One, dreams lead toward Reality, not away from it; they’re a gift to help guide us on our journey of awakening. This view is rooted in Ibn ‘Arabī’s teaching on the Oneness of Being, the multiple “imaginations” of Reality, the mundus Imaginal, and himma or creativity of the heart. For Ibn ‘Arabī’, the highest plane of existence is Reality itself, Absolute Mystery, Light—the Hidden, al-Bātin. All other planes—the world of angels and spirits, the world of souls and ideal forms, the mundus Imaginal or Imaginal world, and the sensory world—are relative existences, imaginations of Reality, shadows of this Light—the Manifest, al-Zāhir. “[Know] that you are an imagination, as is all that you regard as other than yourself an imagination. All [relative] existence is an imagination within an imagination, the only Reality being God.” (Bezels, 125) All that is manifest, including our life in the sensory world, is a dream within a dream.

Though these imaginations are not Reality itself, they contain theophanies, real presences of the One, that can be known through the creative power of the heart. “God created shadows… only as clues for you in knowing yourself and Him, that you might know who you are, your relationship with Him, and His with you.” (Bezels, 126) Like all planes of relative existence, the mundus Imaginal, the plane where spirits are materialized and matter spiritualized, the plane of visions and dreams, is a world of real presences that reveal Light. “The light of this luminous Wisdom extends over the plane of the Imagination, which is the first principle of revelation.” (Bezels 120). In this view, dreams are not fantasies or ego-driven desires. No less real than the sensory world, they too manifest Light. Though we may say it is nothing, Inayat Kahn teaches, “a dream is as real as life on the physical plane.” (Healing, 212)

Because these real presences occur in different forms, however, we have to learn how to interpret them, for what we perceive in one world differs from what we perceive in another world. In the mundus Imaginal, for example, we may see milk or a man. We must receive these not as we know them in the sensory world but according to their “true” form: milk as knowledge, a man as the angel Jabril, “the light of your Lord.” For those who know how to carry forms seen in dreams back to their true form, dreams reveal Light. (Bezels, 123)

We need not subscribe to Ibn ‘Arabī’s metaphysics or dream hermeneutics to appreciate his wisdom for our spiritual practice today: imaginations are central to the way we perceive Reality and ourselves; dream experiences are real; images must be interpreted wisely for them to yield their truth. Far from esoteric, this approach of welcoming dreams aligns with contemporary neuroscience and non-dualistic philosophy, with their exploration of body-mind continuity, feeling and image-making as vital to the emergence of consciousness, and meaning-making-by-combining-images as essential to human being. (See Antonio Damasio’s The Strange Order of Things and Mark Johnson’s The Meaning of the Body.) Recognizing how feeling and non-conscious thought enable us to make sense of the world supports embracing dreams as a way of knowing reality.

Listen, O dearly beloved!

I am the reality of the world, the center of the circumference.

I am the parts and the whole.

I am the will established between Heaven and Earth,

I have created perception in you only in order to be the object of my perception.

If you then perceive me, you perceive yourself.

But you cannot perceive me through yourself.

It is through my eyes that you see me and see yourself,

Through your eyes you cannot see me.

—Ibn ‘Arabī, Book of Theophanies (Corbin, 174)

Some [seed] fell on rocky ground, and when it came up, the plants withered because they had no moisture. (Luke 8:6) Everyone dreams, few of us remember our dreams. This is a loss, for remembering dreams can strengthen the twinned heart of spiritual life: remembering God and remembering our true being. The rabbis say it this way: “If one goes seven days without a dream, he is called evil.” (Berakhot, 55b) When one is not receptive to dreams, one is not open to the creative heart-knowing they invite, one is turning away from the One, the Knower who loves to be known though us. I’ve experienced this. Even when my meditation practice is nourishing, if weeks or months pass without remembering a dream, I feel bereft, as if not quite touching my deepest and widest self, a part of me still skimming surfaces, sleepwalking.

We can train ourselves to remember our dreams. Practices that have helped me include: no media before bed; writing the date in a dream journal and keeping the book open beside the bed; breathing in Ya Bātin and breathing out Ya Zāhir, or praying “Breath of the Merciful, may your seeds of light sown while I sleep take root in my heart and ripen in my being”; upon waking, keeping the eyes closed and not moving or talking; writing the dream down in detail, without editing it or questioning its worth; recording the feeling the dream left me with; giving thanks for the dream. Some suggest writing down a question and placing it under your pillow. Normally I don’t do this, because I avoid directing or limiting my dreaming. For me, dreams are a way of perceiving reality beyond ordinary consciousness, beyond our will and intellect; they’re not answers to questions my ego poses but divine invitations to inquiry into the being-I-am-becoming.

Many techniques for remembering dreams are available—from listening to music to taking Vitamin B6 to inhaling the scent of lavender or mugwort. Find ones that help you catch the seeds sown for you.

Dearly beloved!

I have called you so often and you have not heard me;

I have shown myself to you so often and you have

not seen me….

Why do you not see me? Why do you not hear me?

Why? Why? Why?

—Book of Theophanies (174)

Other seed fell among thorns, which grew up with it and choked the plants. (Luke 8:7) “A dream that is not interpreted is like a letter that is not read.” (Talmud, Berakhot, 55b) We don’t passively receive a truth revealed in dreams; it must be “discovered” by us. (Healing, 214) As the ancient rabbis say, based on the practice of Joseph, the Master of Dreams, dreams “follow the mouth,” the interpreter. The interpreter, however, must know how to discover the truth hidden in a dream, how to “pass from the form of what one sees to something beyond it.” (Bezels, 99)

Interpreting dreams literally, in terms of the sensory world, prevents the unfolding of their deeper truth. Ibn ‘Arabī gives the example of a man who dreamed of drinking milk, woke up, drank a glass of milk, and vomited. If the dreamer had carried the image of milk back to its true form, he would have seen the light shining in the shadow: that he needed to imbibe knowledge. Ibn ‘Arabī even faults Joseph, whom he lauds as a prophet of the Wisdom of Light, for misinterpreting his boyhood dream of the sun, moon, and stars bowing down to him in this way: by reading his brothers’ and father’s submission to him in Egypt years later as the real or sensible meaning of his dream. Ibn ‘Arabī doesn’t offer a “true” interpretation of Joseph’s dream; he simply suggests it has to do with something beyond this life that Joseph had yet to wake up to. His false ego, perhaps, which he had to annihilate if he was ever to receive in love the brothers who abandoned him?

Consulting dream dictionaries can choke dreams too. Their cultural and historical assumptions often mislead, overwhelm, or confuse. For several years, snakes inhabited my dreams. In Jewish dream dictionaries, snakes symbolize deception; in Christian dictionaries, evil, malice; in Muslim dictionaries, enemies, evil, war, deceit, destruction; Native American, wisdom, rebirth, healing; Jungian, the wisdom of the collective unconscious; Freudian, sexuality. How to know which to pursue?

Dream dictionaries also stifle interpretation by speaking generally, not to individuals. Dreams, perhaps more than breathing, visualization, and other spiritual practices, arise from the uniqueness of our being-in-the-process-of becoming, including our body and personality. Even if two people dream the same dream, it must be interpreted differently. “Every individual has a separate language of his dream peculiar to his own nature,” Inayat Kahn teaches, so one must know who dreamed the dream and interpret it “according to his state of evolution, to his occupation, to his ambitions and desires, to his present, his past, and his future, and to his spiritual aspirations.” (Healing, 200). Ibn ‘Arabī lauds Joseph for interpreting the dream of Pharaoh’s baker, his steward, and the Pharaoh himself this way, according to each man’s unique being.

Dream dictionaries share another limitation: the entries are based on concepts, not feelings, and as neuroscientists like Damasio tell us, all images come with feelings associated with them. More than the generalized content of symbols, it is the specific feeling a dream leaves in its wake—relief, terror, disgust, anger, anxiety, frustration, joy, love, peace—that provides a more trustworthy way into its truth.

To discover the truth in my snake dreams, I had to know who I was: a mother living in rural South Carolina where rattlers, cottonmouths, and copperheads frequented our yard; a professor leaving her vocation; a Christian converting to Judaism; a woman confronting childhood abuse and struggling with depression. I had to sink into the feeling that colored the dreams: abject fear. And I had to be wary of any interpretation that did not serve the deepening of my unique being on its path toward the One.

Dearly beloved!

Let us go toward Union.

—Book of Theophanies (175)

Still other seed fell on good soil. It came up and yielded a crop, a hundred times more than was sown. (Luke 8:8) Discovering a truth hidden in dreams depends not on analysis but on the art of inquiry. When we analyze something, the anthropologist Tim Ingold explains, we treat it as an object, a text to decode or translate; we think about dream images, for example, we think after them, looking back to see what meaning they contained. When we inquire into a dream, we think with dream images, looking to the future to see what truth can unfold in our lives. Indigenous hunters, who often dream about the animals they hunt, exemplify the art of inquiry. “To dream like a hunter is to become the creatures you hunt and to see things in the ways they do. It is to open up to new possibilities of being, not to seek closure.” (Making, 11) In the dream the hunter perceives the world in a different way than in ordinary consciousness, and he brings that knowing back to waking life.

Dreams offer us a different way of perceiving reality from the way we ordinarily perceive it. Past, present, and future are compressed, the logic of our daily world is suspended, and we experience reality with different senses, in a different medium, from a different point of view—an animal or tree, the sky or sea. By thinking with a dream experience, we can discover what this different way of perceiving can show us for our lives, how it can guide us in becoming our true selves. Like prophecy, which does not foresee the future but sees the present deeply in order to uncover new possibilities, the art of dream inquiry does not foretell what will or must happen in our lives but leads us deeper into the being we are in the process of becoming, closer to the One.

How can we think with our dreams instead of about them? Each of us must find our own way to heart-think our dreams so they unfold their meaning and ripen in our lives. Several practices have helped me. Each requires you to set aside your will and intellect to give your creative heart over to the dream: you do not work on the dream, to understand it or change it, but allow the dream to work on you. By loosening the grip of the ego and encouraging patient receptivity, these practices help ensure that the waking mind’s eagerness to make sense out of things doesn’t foreclose the dream’s deeper truth. A simple practice is to sit with the feeling a dream left you with. Place that feeling in your heart in meditation and follow where it leads. Another is to place the scene of a dream or an image from it before you in meditation and watch what arises. This is similar to Pir Vilayat’s visualization exercises in Awakening, but using the images your deep self has offered instead of one given to you by a murshid. “Like a doorway opening to that which transpires behind what appears,” he teaches, “an image can lead the psyche into the landscape of the soul.” (59-60) This applies to dream images as well.

Another practice is active imagination, as described by Robert Johnson in Inner Work. Put yourself in a semi-trance, re-enter the dream, look around, and wait until something happens—a character approaches you or talks to you, you find yourself doing or saying something—and then participate in what unfolds, without controlling it. Using this practice on my snake dreams and many others has shown me its creative, healing, and integrating spiritual power. It also taught me experientially the truth of Ibn ‘Arabī’s real presences in the mundus Imaginal. I experienced each active imagination as real, not a movie I was watching in my head but a world I experienced in my body and psyche. I shook with fear, my heart pounded, I sobbed convulsively, I laughed out loud, my skin shivered, I winced in pain, my whole being opened into a smile. There was no doubting the reality of these experiences and their healing effects in my body, psyche, and spirit.

Because I believe most dreams have the potential to yield fruit, I don’t find taxonomies that distinguish true, false, and insignificant dreams helpful. I’m more interested in the variety of ways dream inquiry can guide our being-in-the-process-of-becoming—warning, correcting, rebuking, healing, commanding, summoning, comforting, reassuring, beckoning, creating a way out of no way—and the varying tempos that inquiry can take.

A dream is “the unripe fruit of prophecy,” say the rabbis. (Midrash Rabbah) Some dreams ripen fast. Healing and comforting dreams often do. As a young adult I dreamed I was stuck in a closet, two hand-crocheted dresses hanging before me. One was my size but aqua, my mother’s favorite color. The other was red, my favorite color, but sized for a small child. I stood paralyzed, unable to choose. Then I looked up and saw a purple crocheted bag, flexible and ample enough to hold all that I needed. I woke up healed. In my fifties, in a time of great upheaval, I dreamed of navigating a long, narrow, twisting, rapids-strewn river in a canoe, working hard to survive each new danger. Suddenly I was at the end of the journey, high above a canyon, by a waterfall, looking back at the entire sweep of the river, overwhelmed by the beauty of it of it all. I woke up in peace. “Spiritual progress is the changing of the point of view,” says Inayat Khan. (Inner Life, 133) In shifting my perspective, these dreams transformed my life.

Some dreams ripen over years or decades. Dreams I had in my twenties about concentration camps and Jewish refugees sailing on a tiny raft to Israel; dreams in my thirties about Jesus drowning in a dungeon prison and Joan of Arc fighting inside a dark cathedral, laying down her sword, and walking outside into the sunshine; and dreams in my fifties about Khidr dancing wildly—all unfolded slowly to guide me on my path.

Dream inquiry is a dangerous art. To practice it wisely requires patience and humility. It takes years of welcoming and working with our dreams to become familiar with their peculiar language for us. And our interpretation deepens and widens as our hearts do. The boy Joseph who interpreted his dream of the sun, moon, and stars bowing down to him was not the mature, awakened Joseph who was able to set himself aside to interpret the dreams of others. Also, as with every practice, the art of dream inquiry is not immune to the tricks of the ego, that enthralling illusion. Recently, while dreaming, I heard, “Be ready for the call.” For months I believed this promised the arrival of a career opportunity, and I taped the words over my desk to give me hope. After a shocking early morning phone call informing me of my younger sister’s untimely death, I believed the dream’s true meaning had been revealed. Now I hear these words differently; they’re a knock on the door of my heart: Wake up!

The art of dream inquiry may be the most mysterious art of all, but if we nurture our creative heart and dare this spiritual practice, it can guide us on our journey of awakening.

To sleep, perchance to dream; to dream, perchance to wake.

NOTES

1 Joel Covitz, Visions of the Night: A Study of Jewish Dream Interpretation. Boston: Shambala, 1990.

2 Henry Corbin, Alone with the Alone; Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn ‘Arabī. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969.

3 Ibn ‘Arabī, The Bezels of Wisdom. Tr. R.W. J. Austin. New York: Paulist Press, 1980.

4 Tim Ingold, Making: Anthropology, Archeology, Art and Architecture. New York, 2013.

5 Robert A. Johnson, Inner Work: Using Dreams and Active Imagination for Personal Growth. HarperSanFrancisco, l986.

6 Hazrat Inayat Khan, Healing; Mental Purification; The Mind World. Surry: Servire, 1978.

7 The Inner Life. Boston: Shambala, 1997.

8 Pir Vilayat Inayat Khan, Awakening: A Sufi Experience. New York: Tarcher/Putnam, 1999.

[/wcm_restrict]

ARTWORK © MICHELLE BLADE

[wcm_restrict plans="Sufi Journal Digital Edition, Sufi Journal Digital Edition old"]

RETURN TO ISSUE 97 TABLE OF CONTENTS

[/wcm_restrict]

[wcm_nonmember]

To read this article in full, you must Buy Digital Subscription, or log in if you are a subscriber.

[/wcm_nonmember]

ne of the first to bring Bön teachings to the West, in 1988 he was invited by the Dzogchen master Chögyal Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche to teach in Italy, which brought additional opportunities to teach in other locations throughout western Europe. In 1991 he was awarded a Rockefeller Fellowship at Rice University in Houston, Texas, and continued research into early Bön tantric deities and their relationship to Buddhist traditions in early Buddhist Tibet.

ne of the first to bring Bön teachings to the West, in 1988 he was invited by the Dzogchen master Chögyal Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche to teach in Italy, which brought additional opportunities to teach in other locations throughout western Europe. In 1991 he was awarded a Rockefeller Fellowship at Rice University in Houston, Texas, and continued research into early Bön tantric deities and their relationship to Buddhist traditions in early Buddhist Tibet.

Pictures on My Eyelids

Pictures on My Eyelids

Through the Looking Glass

Through the Looking Glass

The Art of Dream Inquiry

The Art of Dream Inquiry