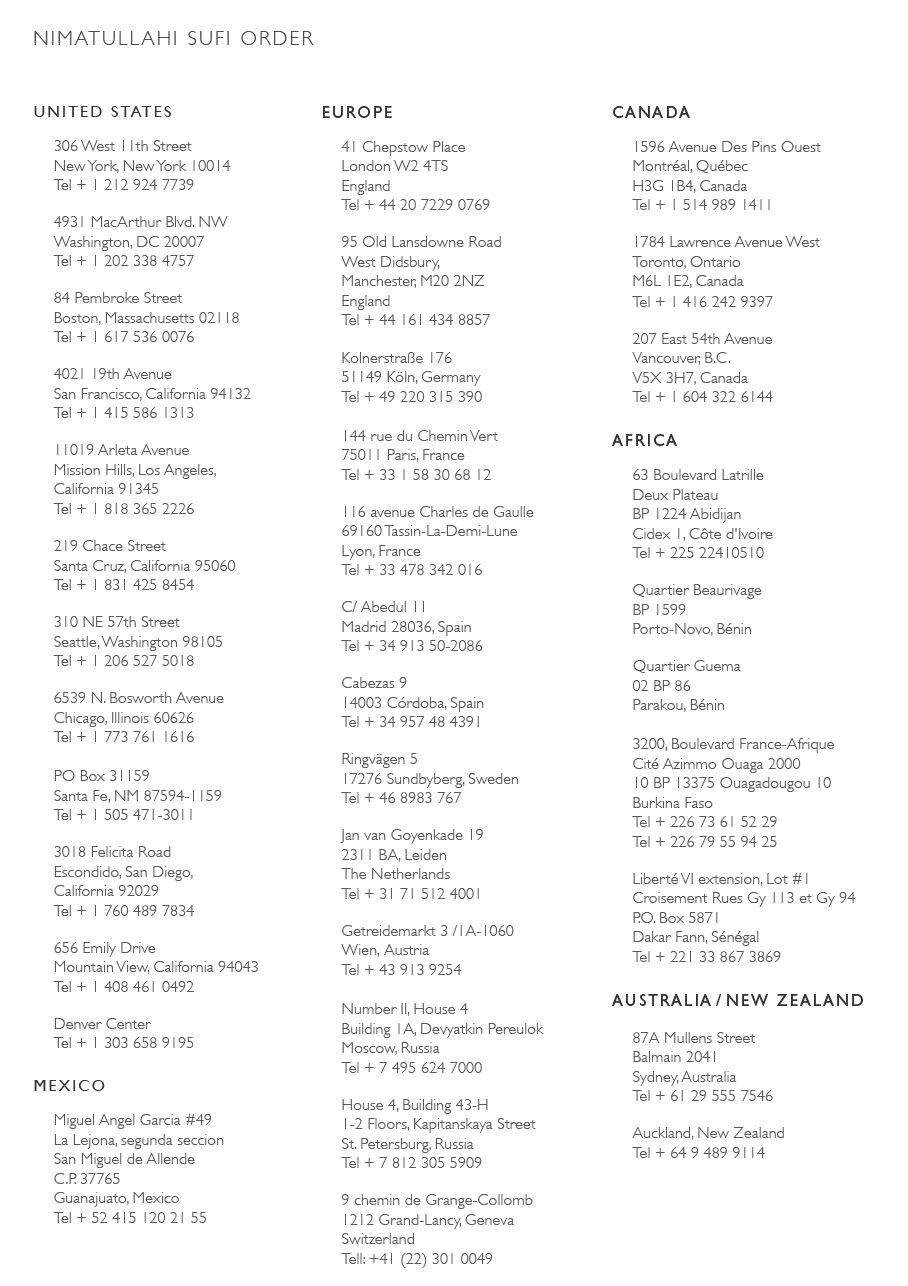

HAFEZ

The Earthly Sky-Walker

BUILDING OUR SPACE IN A SHIFTING UNIVERSE

By FATEMEH KESHAVARZ

Until a couple of centuries ago, humanity lived in an orderly and divine-centered universe. Famously, the ability to be enchanted, amazed, and bewildered started to elude us when brilliant minds such as Newton’s began to exchange that enchanting world for one entailed in—and explicable through—the laws of classical physics. After all, life is movement in time and space. If differential equations can calculate the trajectory of all moving objects forever (given their mass, velocity, and such), are there potentially unknowable forces to be enraptured with?

The ride has been rough: we’ve seen the collapse of our older grand narratives, and the need to make sense of the evolutionary adaptation strategies of our complex biosphere. That is not to mention the existential loneliness in a universe which no longer seems to have a grand custodian. In the meantime, classical physics continues to search for a grand theory that can explain everything in one fell swoop, a quest which the biologist and complex theorist Stuart Kauffman has described as comparable to our strong pull toward monotheism.1

Interestingly, the total surrender to an entailed universe has been countered by science itself. Complex theorists have proposed that a scientific study of our amazing biosphere—in the most rudimentary manner—indicates that even on our relatively small planet, life unfolds in endlessly new and unpredictable ways. Every moment new adjacent possible opportunities are enabled by evolutionary conditions that blossom into new actualities. These new actuals themselves enable other unprestatable possibilities—to use the philosophical idiom—that in time develop into unforeseeable actuals. And so continues the story of life on earth, a “persistent becoming” beyond our knowing. I hope it is beginning to become apparent why we must invite the likes of Hafez, the 14th-century poet of Shiraz, with a propensity for building poetic divine spaces, into this conversation. Still, let me put my spin on it.2

[wcm_restrict plans="Sufi Journal Digital Edition, Sufi Journal Digital Edition old"]

It is rather simple. We can look forward to being enchanted once more. We can envision our humble earth as a site for the “radical emergence,” which biologists like Kaufmann describe as the “persistent becoming beyond our knowing.” We can simply call it life and acknowledge the fact that the last thing we want to do is to deprive ourselves of a direct encounter with this ever-unfolding possibility which is nothing if not “enchanting.”3

Allow me to echo what the French philosopher, Gaston Bachelard, proposed brilliantly a few decades ago. This encounter with life could, even should, he suggested, be a poetic one. When grappling with hefty existential questions, Bachelard observed, poetic imagination gives us the tool for an ontological amplification of our beings—philosophical shorthand for learning to see the expansive dimensions of our being and that of our being-in-the-world.4 After all, most poetic traditions compare poetry itself to a space to be inhabited by the poet and subsequently, the reader. In Latin, stanza means a room and in Persian and Arabic the word bayt denotes a house and a verse at the same time.

What is the best way to place ourselves in an immediate and engaging position with this “radically emergent” enchanting life force which will defy the notion of an “entailed” universe? Without pretending that there is only one answer, this paper suggests following in the footsteps of genius artistic creators such as Hafez, poets in the business of ontological amplification of our human existence. Hafez, who lived from 1325 to 1390 in the historic city of Shiraz in south west of Iran, made a habit of engaging life emerging all around him to give voice to his urge to make sense of its complexity and beauty. Like other poets of his caliber, he broke out of our limited imaginings of space and time to explore expanded notions of the world and fresh ways of connecting with it. In the process, Hafez lent his readers not just a pair of new eyes but also tools for connectivity, healing and growth.

I would go a step further. The poetic recreations of space (the divine echoes in them included) by the likes of Hafez are not merely evocative, preserving, or poetic acts. Their function goes beyond pointing to the beauty and intricacy of the world we often fail to see. Rather, they are constitutive of the spaces that we envision ourselves able to build and inhabit. Indeed, frequently, they encourage us to imagine and therefore construct such spaces. In that sense, they may be daring exercises in building worlds in which the border between the subjective and the objective are intentionally blurred. Let us start with a superb example of world building done by a much later western poet, Victor Hugo. In a passage from “The Rein” which Gaston Bachelard highlights, Hugo writes:

“In Freiburg I forgot for a long time the vast landscape spread before me in my preoccupation with the plot of grass on which I was seated, atop a wild little knoll on the hill. Here, too, was an entire world. Beetles were advancing slowly under deep fibers of vegetation; parasol-shaped hemlock flowers imitated the pines of Italy…, a poor, wet bumble-bee, in black and yellow velvet, was laboriously climbing up a thorny branch, while thick clouds of gnats kept the daylight from him.” 5

This beautiful exercise in natural world-building can transport us straight to a similar poetic construction site by Hafez—with some differences. Hafez starts simple, builds brick by brick (word by word, if you like) and adds subjective layers along the way. This enables him to move between the inner and the outer worlds often and with ease. In the process, he constructs bridges and doors that connect the two in a rather matter-of-fact way:

My heart forgets the green landscape when it sees the moon of your face aglow.

For like a cypress, it [my heart] is bound to earth, and like a tulip’s red heart, it is filled with sorrow.

To make sure that we have noticed the co-existence of the inner and outer geographies, here reflected in the beloved’s beauty and the heart’s sorrow, he highlights the tension between the two, the deep interconnection that sometimes reveals itself in a confrontational manner:

The inner world of hermits does not owe anything to the physical world.

We do not bow, not even before the prayer niche of an arched eyebrow.

A claim easily refuted by its own central image—an arched eyebrow—not to mention the first verse: the earthbound heart forgetting its captivity with a glance at the beloved’s moon-like face. Then, we are outside again:

Look at the violet! It compares itself to her dark perfumed curls.

A simple servant and such extraordinary designs!

Come to the garden and see that next to the rose’s thrown

Tulip stands like a royal attendant holding a goblet of wine.

As we navigate this inner/outer dialectic in which the freshness and color of the outer is contrasted to the melancholic ambience of the inner, Hafez appears to be underlining the asymmetry of the two. Riding the flow of the words, we allow the rhythm of the verses take us where they will.

As is often the case, the quiet is the sign of a brewing storm. Sure enough, in the fifth line a massive dark space opens before us rather abruptly—all the more striking due to its sudden disruptive nature. Interestingly, what stops us in our tracks is not a deepening gap between the inner and outer, but rather the strong overlap between the two. Hafez exposes the limits of the images which we may so far have adopted to understand either of the two realms. This verse begins with شب ظلمت و بیابان “the night of darkness, and the desert.” Note that it is not ظلمت شب و بیابان “the darkness of the night and the desert” as one would normally expect. But rather it is the night of darkness. The move from the concrete to the abstract underlines the vastly undefinable nature of the night, a feature that it shares with the fear of being lost in the desert. The desert, the night, and the fear, the outer and the inner are all merged:

The night of darkness, and the desert, where can one go …unless.

The word “unless” signals the existence of a safe destination reachable in the dark. And sure enough it comes in the most ordinary commonplace language, the beloved’s visage concretized into a lamp placed above the dark road:

The night of darkness, and the desert, where can we go…

Unless your face holds a lamp to light up the road.

The animate and inanimate come together at the end of the poem. Hafez and the candle—which has to be put out at dawn—are crying together.

Most significant for our discussion is the poem’s ability to transform the poetic space it opens before the reader. The merging of the seemingly incompatible inner and the outer as well as the concrete and the abstract are not mere poetic strategies to achieve artistic effect (though that is a goal too). Rather, these dynamics transform the space from descriptive to disruptive and ultimately transformative with regard to our expectations. In more radical instances, below, such poetic dialogues with the divine become constitutive of the personality and the role of the poet/lover, an opportunity open to the reader as well.

But first, why do we need to do anything about our understanding of space? We appear to have astonishing control of space, and many vantage points to look from. For the first time in human history, we are commanding the skies, the ocean floors, the earth’s deep molten core, and particles so small we did not know they existed. We can traverse distances and communicate across borders and barriers in ways unimaginable to our ancestors only a century ago.

Well, perhaps these very gigantic steps forward are responsible for blinding us to what we lose on a daily basis. Our access to physical space, for example, is being reduced and regulated in favor of comfort, speed, and efficiency. While cars, trains, and planes protect us from the elements, our urban movements are Uberized to predict distance, route, duration, and cost. No surprises, confusions, or discomforts along the way. We may soon forget how it feels to be lost in an unfamiliar location. On a parallel note, poverty is neatly cut out of desirable spaces and ghettoized to invisibility while refugees are mostly barred from spaces of prosperity and safety. As heaven and earth have remained disconnected since the age of reason, so are the opposing realms of danger and safety, comfort and discomfort, efficiency and idle exploration. We have built walls and plan to build more but hardly ever ask “Who will be barring whom?” What will our walls do to us, and to our understanding of the inner and the outer worlds?

There is the internet travel to be sure. But there too, the search engines plot much of the course of our visits based on our previous choices. We like finding more of what we liked before. They like selling us what we like. That which has escaped them, we cut out of the picture exercising our user privilege for surfing safe cyber territories frequented by likeminded others. The combination imposes severe limits on what can otherwise be a new universe to discover.

Add to the mix what the philosopher Richard Kearney calls “our need for the inner spaces of reverie and meditation,” and our urge for revisiting our inner “basements and attics.” The need for the journey is obvious, not just to explore our inner deserts, green pastures, stormy seas, and quiet blue skies—but in order to learn to become the architect of our own world… to build it and to fill it with transformative echoes.6

Let us return to Hafez by way of a ghazal centered on the significance of interlocutors, those with speaking voices with transformative echoes. For Hafez, these are often lovers who can tell the tale of their intimate experiences with the beloved effectively, a beloved always interchangeable with the Divine:

Taking in your sweet scent that spreads in the breeze of Saba

Is like listening to the tale of love told by a loving friend.

Much unfolds in this opening verse. In a world silenced by perils, speaking about love is what we desperately need. Or, life is a tale that must be told with genuine love and care. That is what the breeze does when it brings the beloved’s scent. By the same token, not every tale is worth telling, particularly those we take a false pride in. Such tales disappear from the world’s memory in no time:

King of beauty! Throw a glance at this beggar—when you can.

For numerous are tales of beggars and kings long forgotten!

In short, take a careful look at the one who loves you, for love is what gives your story meaning. Introducing kings and beggars, and living one’s life genuinely, gives Hafez the occasion for evoking social issues. He will never let this opportunity go to waste. Such issues plague his time, and there is one he is particularly annoyed with: acts of piety performed to deceive the masses and seize political power. The genre of ghazal gives the poet the freedom to move between themes and construct new poetic sites. A spiritual sanctuary is what Hafez chooses to build next. But to our shock, the site highlights the significance of a highly irreligious act, drinking wine:

I use wine to revive the inner faculties of my soul.

For I have sensed the scent of hypocrisy in the houses of worship.

Then, comes the punchline, the shah bayt, “the king of the verses” as Persian speakers call it. It is usually the most celebrated line in a ghazal. The shah bayt of this poem is known to almost any Hafez lover. And we are now in an infamous space built next to a standard place of worship, a wine shop:

Where did the wine-seller learn the divine mystery?

Tell me that!

For the religious masters do not share their secret with ordinary folk.

Various questions arise. Who is this wine-merchant-turned-divine, the simple shopkeeper on the block, who runs the counter space to all houses of worship and piety? How did he hear the divine mystery? How did he establish his personal line of communication with the almighty? And the elitist religious master, who denies him and other simple folk that secret, he must be cold and callous. Maybe he did not have the secret in the first place. Worse still, maybe he only pretended he did. These and similar unanswerable questions have hovered in the minds of Hafez readers for centuries. Again, their powerful impact on the reader’s mind and their persistence in the social imaginary are results of not having a clear answer. It is safe to assume that Hafez cared more for planting questions than finding answers. Nonetheless, there is one question he wishes to address: the identity of the wine-seller:

God, can I ever find a confidant with whom my heart

Would share the intimate conversations it has enjoyed with you?

Although somewhat ambiguous, the parallel between the beautiful verses that our poet is giving us, his conversations with the divine, and the wine that revives the “inner faculties,” are unmistakable. Besides, in lyrically expressed true love, the longing never ends. He longs for the conversations and we long for hearing them. We will never truly know if he is the wine-seller who knows the divine mystery or not, but we take charge of our own journey as we read them.

But there is a catch. The melancholy in the beloved’s response indicates that such interactions with the divine are not always carefree and triumphant. Love’s wayfarer, like all journeyers, must face the hardships of the road. “My devoted heart,” دل حق گزار من , Hafez continues, “deserved better than the harsh words” that it received from his companion. And yet, the complaint is not tinted with isolation. All humanity shares the suffering, for “Nobody has ever sensed the scent of loyalty in the gardens of this world.”

This is a moment of anguish as well as possibility! The breeze has spread the scent/told the tale of love, Hafez has opted for wine to revive his inner faculties, and the wine-seller/Hafez has held intimate conversations with the divine unbeknownst to the religious master. At the same time, the companion uttered harsh words. Can the bliss in the journey come to nothing? Can the beloved withhold his/her approval? We linger in this melancholic moment—for, remember the word bayt “verse” also means a house, a place in which you can stay. And sure enough, we are rewarded with the revelation of a secret, one of a somewhat transformative nature —though it resembles a simple announcement. The message: there will always be only one true story-teller, love itself:

Come cup-bearer! Come and listen!

For love proclaims openly:

“Those who speak about me repeat what I have told them!”

The announcement is both simple and complicated. Its power and complexity come from the strong poetic tradition in which it is rooted. By the time Hafez arrives, the tradition has already established and celebrated the rule of love. When you are exposed to the alchemy of love, you are transformed. From that moment on, you are immune to much that afflicts others. You will not be defeated—because nothing can destroy your spirits. You will not hate—because everybody is part of the lifecycle of love. You cannot say the wrong thing because you cannot be less than genuine. You will not take false pride in your accomplishments—because who cares what you have or have not accomplished. And you will not make mistakes—because love will guide you. You take a look at yourself and realize that love is the speech, the speaker and the listener. Love is all there is.

This is a small example of the ways in which conversations with the Divine open up new spaces within the possibilities of each verse in each poem. In that space, events, occasions, and individuals are transformed. These exchanges/utterances go beyond observation, reporting, or musing. They have the feeling of an encounter invigorated with wonder and astonishment. Their conversational flow replaces the monotony and indifference of factual reporting. In a gentle but fundamental way, they disrupt our expectations and perceptions including the very definition of the sacred itself. And since each reader builds his/her space for the wondrous encounters, the architecture of possibilities is as diverse as the readers.

NOTES

1 Stuart Kauffman, Humanity in a Creative Universe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

2 Stuart Kauffman, Humanity in a Creative Universe, 20.

3 Kauffman, ibid.

4 Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space. Tr. Maria Jolas (New York: Penguin Books, 2014), 179 (originally published in the US in 1964).

5 Bachelard, ibid.

6 Quoted in Bachelard, Poetics of Space, ibid, p. 170.

[/wcm_restrict]

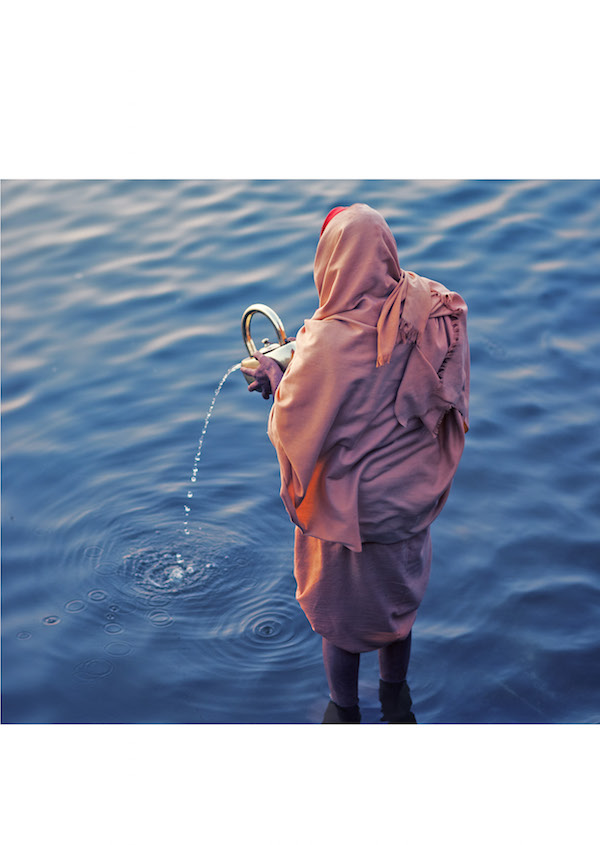

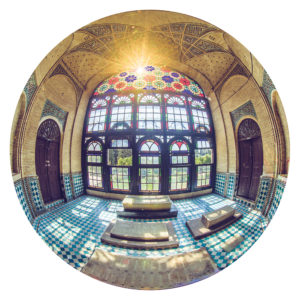

PHOTO © MOHAMMAD REZA DOMIRI GANJI

PHOTO © MOSTAFAMERAJI / WIKIMEDIACOMMONS.ORG

[wcm_restrict plans="Sufi Journal Digital Edition, Sufi Journal Digital Edition old"]

RETURN TO ISSUE 95 TABLE OF CONTENTS

[/wcm_restrict]

[wcm_nonmember]To read this article in full, you must

Buy Digital Subscription, or

log in if you are a subscriber.[/wcm_nonmember]