THE GREATER PRAYER OF BEING

By MARK NEPO

In Quakerism, whatever you believe needs to be grounded in the evidence of your own life. In Quakerism, [there’s an] insistence that everyone has within himself or herself a source of truth—an inner light or inner teacher. Of course, truth is not the only thing we hear from within. We also hear the voices of ego, of fear, of greed, of depression. So Quakerism puts an equal emphasis on the role of community in helping people sort out what they’re hearing.*

—Parker Palmer

This is the greater prayer of being: how we take form and grow where we are,

only to be dissolved into a greater union with the life around us.

Each of us walks about in a cloud of affections: our love, our pain, our desires, our history. Then, we need help from each other to outwait the cloud, so we can regain our direct experience of life. We need to break the trance of what we want or wish for or regret. The task is not to replay what we go through, but to integrate what enters our heart. Not to linger in what might have been or what has fallen short, but to make the most of what’s before us. The challenge is to feel what’s real while it’s real.

And we each need help sorting what we’re hearing. For fear and worry are dark spiders constantly weaving webs in the corners of our mind, till one day we walk into those webs, surprised and entangled. This is why we have to still our mind and open our heart: to clean out the webs of fear and worry. Otherwise, a dark gauze grows between life and us. But love sweeps through the gauze, and honest inquiry sweeps through the cobwebs. So just as we need to dust our home, we need an inner practice to dust our mind of all the webs we spin.

[wcm_restrict plans="Sufi Journal Digital Edition, Sufi Journal Digital Edition old"]

When overwhelmed by worry, fear, or regret, we start to disempower where we are, by pining to live in the future or the past. The urban dictionary has a contemporary expression of this painful yearning, the word “fomo”, which is an acronym for fear of missing out. This is considered a symptom of digital withdrawal, a state of anxiety that arises from feeling bereft and even panicked at not having access to the Internet, to calls or texts, to Facebook or Twitter. This is a modern expression of the underlying sense that humans have struggled with forever: that life is happening without us. This perilous inner state arises from investing our being in the hope that, “If I could only get over there, then life would be worth living.”

But when we can sort what we’re hearing and outwait the cloud of our affections, we land in the beautiful if gritty terrain of where we are. Now caring for each other can restore us. Once grounded enough to truly care, then I can love you. And the depth of that love dissolves images of life being “over there.” Then, my singular sense of self starts to let others in, so that when you’re in pain, I’m in pain. And when you’re overflowing with wonder, I’m saturated with that wonder. This is how life grows and joins, a pain at a time, a wonder at a time—despite our clouds of affection, our webs of fear and worry, and our fear of missing out. This is the greater prayer of being: how we take form and grow where we are, only to be dissolved into a greater union with the life around us.

This brings to mind the story of two sisters who were very close, and very competitive. Lisa, the older, was obsessed with being exceptional. She needed to excel in everything. Gail, the younger, was obsessed with experience. She needed to meet as much of life as she could. Gail would question Lisa, “Why all the work to make things happen?” And Lisa would question Gail, “Will you ever accomplish anything?” They never really understood each other, though they secretly envied each other’s devotion. It was later in life, after many years apart, that Lisa fell ill and Gail came to care for her. Forced by her illness to be still, Lisa could no longer accomplish anything. It made her feel lost but opened her to her deeper self. And forced by her love for Lisa, Gail had to become competent in her care, accomplishing a great deal from day to day. It was the fragility of life that stopped Lisa and Gail from insisting on the face each showed the world. They met in the quiet moments of one caring for the other.

Each of us is scoured over time, though we hate the scouring; hollowed to something beautiful, though we fear the hollowing. Each of us is hovered over by unseen angels and demons who want our attention. Each of us, worn to a small chamber in which what matters can be heard despite the noise we make while running to and from. This scouring by angels and hollowing by demons is how we’re refined while here, no matter how clouded and lost we may get along the way.

Just the other day, I was trying to outwait the cloud of my own affections. The January sun was splaying through the anatomy of trees. My dog was sniffing about, scenting mice gone underground. The only noise was the snort of her nose in snow. I was drawn again to the bare tops of trees, thinner than the rest. Drawn to the life of the tree moving all that way from the gnarly, buried root, stretching up the trunk, and twisting through the limbs, to the most exposed gesture reaching to the sky.

Then, I could see that, like the length of a mature tree, from root to leafless tip, this is how we establish ourselves in the world. The deeper our roots, the higher we can reach. Now I wonder, if trees could talk, would they tell us that their roots feel the wind from the sky and that their uppermost twigs feel the earth packed around their roots?

When taking root where we are and reaching toward the light, we too feel everything all the way through. The clouds were drifting by, more visible because of the windblown twigs, just as the Truth of the Universe is more visible when we are fully here.

*“In Quakerism…” From an interview with Parker Palmer by Alicia Von Stamwitz, “If Only We Would Listen” in The Sun. Chapel Hill, NC, Issue 443, November 2012, p. 12.

A thousand masks

No matter where I’m drawn to go, it always leads to Here. For every effort to seek

or run only lands me in the timeless Center that lives under all journeys.

The world has a thousand masks which taken off, one at a time, reveal the faceless

face of Spirit that keeps everything alive. How do I know this? I can’t really say.

Except that being broken and lifted have peeled off my masks. And those I love,

when exhausted or awakened, have put down their stories. And then, we’re as

naked as the animals who quiver in the stillness between night and day when the

softest breeze makes them stare so widely into the Bareness of Everything,

just waiting beneath the mask of nothing.

MARK NEPO

[/wcm_restrict]

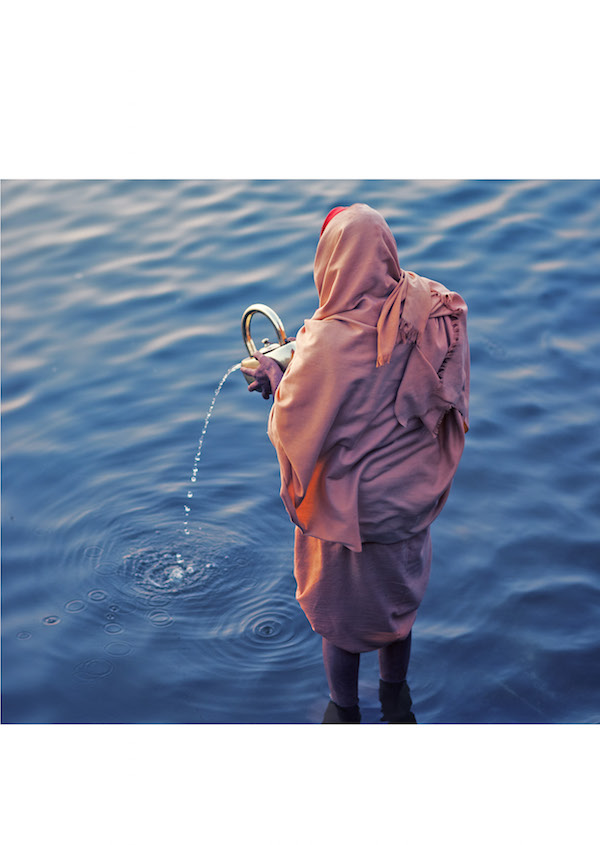

PHOTO © PAUL ZWIRS / 500px.com

PHOTO © PURIPAT / bigstock.com

[wcm_restrict plans="Sufi Journal Digital Edition, Sufi Journal Digital Edition old"]

<a href=”https://www.sufijournal.org/95-table-contents/”>RETURN TO ISSUE 95 TABLE OF CONTENTS</a>

[/wcm_restrict]

[wcm_nonmember]To read this article in full, you must

Buy Digital Subscription, or

log in if you are a subscriber.[/wcm_nonmember]

Of Other Spaces

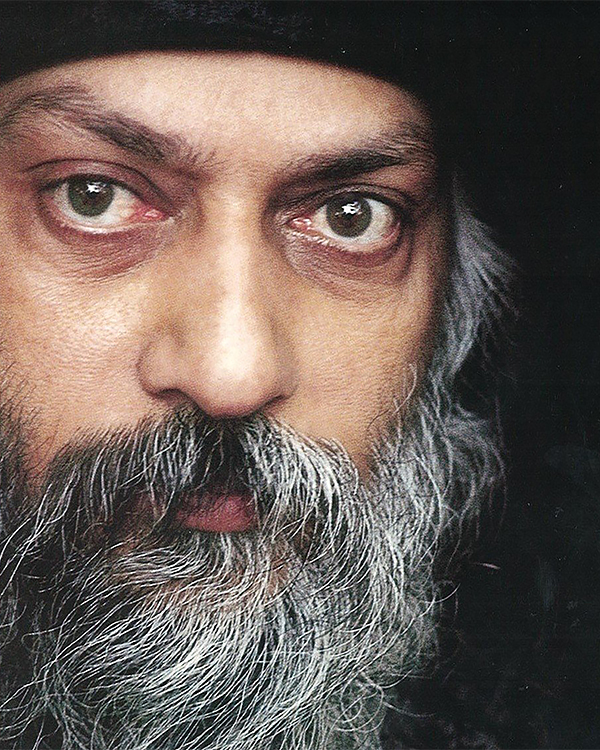

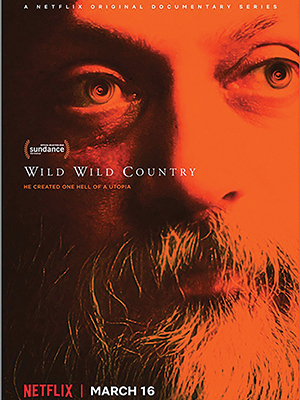

Of Other Spaces Rajneeshees arrived in Oregon during the height of cult hysteria, just a few years after the Jonestown incident and before the Waco tragedy. The 1980s and the 1990s mark an important phase in late formations of American secularism as a mode of governance that increasingly attempts to shape, regulate, and monitor religion on the basis of racialized Christian values. In a way, Rajneeshpuram became the space through which secularism in the United States realized, exercised, and revealed its Xenophobic nature. The very genealogy of the emergence of the cult-religion dichotomy surfaces in extensive interviews with Antelopeans who legitimize their hostility towards the Rajneeshees through branding them as a sex-crazed Indian cult. Once the conflict snowballs into a massive battle at the national level, with FBI agents at its centerpiece, the series raises broader questions about the role of the state in constituting and policing religion. But there are more layers to the story of the fate of this commune.

Rajneeshees arrived in Oregon during the height of cult hysteria, just a few years after the Jonestown incident and before the Waco tragedy. The 1980s and the 1990s mark an important phase in late formations of American secularism as a mode of governance that increasingly attempts to shape, regulate, and monitor religion on the basis of racialized Christian values. In a way, Rajneeshpuram became the space through which secularism in the United States realized, exercised, and revealed its Xenophobic nature. The very genealogy of the emergence of the cult-religion dichotomy surfaces in extensive interviews with Antelopeans who legitimize their hostility towards the Rajneeshees through branding them as a sex-crazed Indian cult. Once the conflict snowballs into a massive battle at the national level, with FBI agents at its centerpiece, the series raises broader questions about the role of the state in constituting and policing religion. But there are more layers to the story of the fate of this commune.