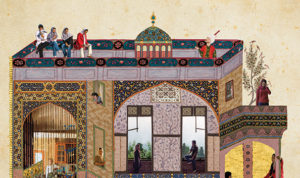

Among other things, the hagiographies of Abu Sa’id shed some light on the segregation of the sexes in the Sufi lodges (khaneqahs) in the 5th and 6th centuries (11th and 12th CE). We have references to women attending Abu Sa’id’s lectures and the sama’ sessions on the rooftop. This means that Abu Sa’id and his male congregation were seated in a courtyard and the presence of women on the rooftop created a spatial arrangement that gave women a visual advantage; they could look down and see the men in the courtyard whereas men, even if they looked up, could only see indistinguishable veiled women sitting on the rooftop. So if we followed the direction of the gaze from the rooftop to the courtyard, from the women onlookers to the male participants, it was as if the men were on a stage playing to the female audience. However, the dynamics of spectatorship and surveillance are activated in both directions. The fact that the women have a better view of the men’s bodies does not mean that their gaze is more comprehensive or powerful, although according to what follows, that was certainly a fear, if a projected one, of the male teachers.

However, the possibility of sama’ as a male performance in a courtyard for a female audience sitting on a rooftop raises questions about women’s participation in Sufi rituals and whether or not women are mostly understood as audiences rather than practitioners of Sufi rituals. The segregation of the sexes in the public spaces like the Sufi houses and a religious/cultural prohibition against women singing and dancing in public gatherings during the formative years of Sufism (roughly from the 3rd to 5th century the 9th to 11th century CE), forces the male gender to embody the Sufi ritual of sama’ and creates a possibility of a gendered division/dichotomy between the performers and the audience members. In fact, one can argue that the performativity of sama’ begins with the women’s gaze from the rooftop and her special positioning as an audience. Buy the current issue to read the entire article.

artwork ©Soody Sharifi