BEYOND MATERIALISM

An Interview with Bernardo Kastrup

By Neil Johnston

Bernardo Kastrup is a metaphysical philosopher with a PhD in Computer Engineering, specializing in artificial intelligence and reconfigurable computing. He has worked in some of the world’s foremost research laboratories, including the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) and Philips Research, and his writings explore the “thoughtscapes” of philosophy of mind, ontology, neuroscience of consciousness, psychology, foundations of physics and philosophy of life.

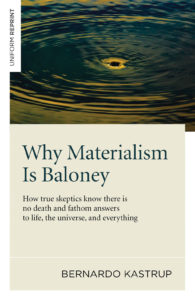

He has a penchant for oxymorons and thought experiments. His published titles—Meaning in Absurdity, Dreamed up Reality, Rationalist Spiritualty, More than Allegory, Brief Peeks Beyond, and Why Materialism is Baloney—embody spectrums of thought and experience, always reaching for something beyond the “known” that calls to be touched; the space between extremes that paves a middle way into a fruitful no man’s land of “metaphysical speculation.”

[wcm_restrict plans="Sufi Journal Digital Edition, Sufi Journal Digital Edition old"]

Neil Johnston: In your book Why Materialism is Baloney you’ve mounted a rigorous challenge to materialism as being the principal ontology underpinning mainstream western philosophy. Is it possible to outline the basis of your challenge? Materialism or mainstream physicalism, as it is technically called, is based on the concept of matter as the ontological primitive, in other words, a real entity, something of substance, something that exists, but it exists outside and independent of consciousness. According to materialists, particular arrangements of matter somehow generate consciousness and the contents of experience. However, matter outside consciousness is not an empirical fact. It’s not available to us as such. The only thing that is available to us is perception, and perception is mental in nature, not material. This idea of matter as something independent of consciousness is only an explanatory model. It tries to answer this question: If this world isn’t outside consciousness, how come we are all sharing perceptions of the same world?

Ok. But the overriding influence of materialism has profoundly shaped modern civilization. Yes, but is materialism the cause or is it a reflection of a development in the psychology of Western civilization that led both to certain materialist tendencies and to an articulation of a worldview—the philosophy of materialism—to justify those tendencies? On the face of it, materialism is so absurd that it’s impossible for me to believe that it has won out purely on the basis of the soundness of its argument. Materialism in a nutshell basically means the following: my mind conceptualizes something—namely, matter—within itself; it then claims this matter to be outside itself; it then points at this matter and says “I am that!” I mean, it’s completely outrageous, it’s absurd and it fails to explain the only thing that we actually know for sure, which is the qualities of experience. And yet it has become the mainstream narrative about the nature of reality.

Meanwhile, the materialist tenets that deny universal consciousness are set against the study and experience of consciousness by diverse numbers of traditions—a whole religious, spiritual, and cultural canon which presupposes an awareness of human consciousness and its relationship to universal consciousness. Yes, this awareness precedes materialism by millennia, it’s thousands of years old. So, materialism is a very new kid on the block. I don’t think it’s going to survive very long. As a matter of fact, I think it’s collapsing right now. [laughs.]

The thing about religious and spiritual traditions is that they employ metaphor rather than pseudo philosophic/scientific analysis to identify the existence of human self-consciousness and its relation to universal consciousness. Your book Why Materialism is Baloney, has a very powerful set of metaphors for consciousness and egoic representation in the mind which we’ll come to, but there are many others that relate to the relationship between self and universal consciousness; metaphors for essence and emptiness; mystical immersion; drop and ocean, for example. Metaphor appears in many spiritual traditions to describe ways of experiencing consciousness, where the subjective and self-conscious ego is a filtered experience of universal consciousness itself. And many practices make the conscious dissolution of the ego an overriding condition of experiencing universal consciousness. In Sufism for example, that relationship is present through the Lover/Beloved motif which introduces an emotional force of love. The Lover/ego-consciousness falls in love with the Beloved/universal consciousness, a process of emotional attraction to a non-self-consciousness that reduces ego-consciousness. So, the question is: how does this emotional/feeling correspondence between self-consciousness and universal consciousness relate to your theory of consciousness? You talked about metaphors. Indeed, I make liberal use of metaphors as do the world’s spiritual traditions because they convey knowledge by acquaintance, a mental gestalt, not merely to convince you that something is conceptually right. A conceptual model is something indirect. You may be convinced the model is correct, and still not know by acquaintance what the implication of that model is. Søren Kierkegaard, the Danish philosopher, used to say that you can build a conceptual system, but so long as you don’t inhabit the system you built, you are like an architect who builds a castle and lives in the barn outside. And I think that’s a great metaphor, there you go…

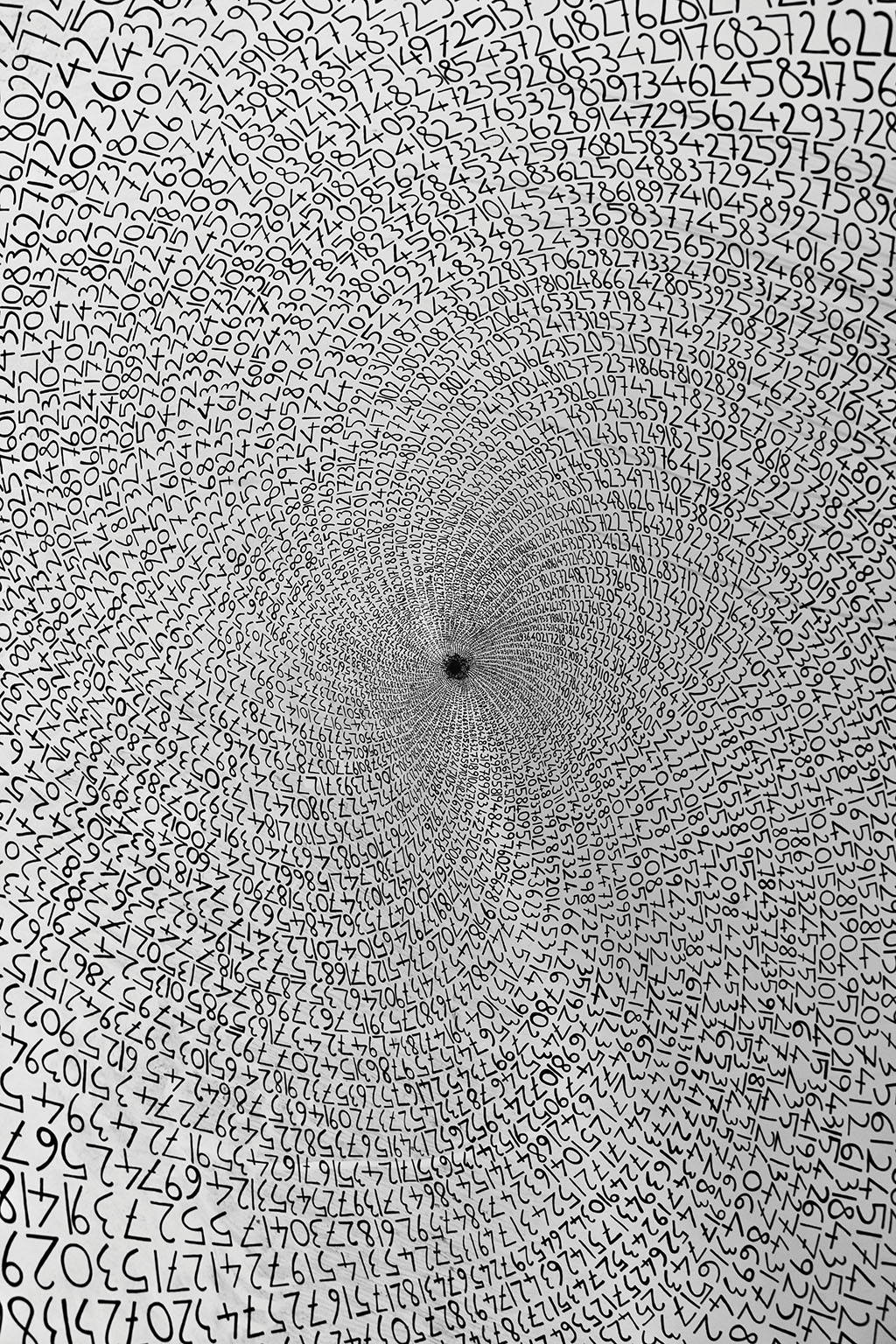

It’s a great metaphor. Science is also operating in terms of metaphors. The only difference is that it does not recognize what it does as metaphoric. While the world’s spiritual traditions are very open about it and they say this is just a metaphor, we are trying to point to the moon, but don’t look at the finger, look to the moon, materialism is saying the moon is in the finger because it isn’t a metaphor, it’s literally true, there is no “moon” outside the finger. This is, if you will forgive my English, bullshit. It’s complete nonsense. In the philosophy of science we have this movement called anti-realism and what it does is to deny literalism. According to anti-realism, what science does is to build “as-if” models. Take, for example, things not immediately available to experience, like an electron. You never see an electron. You see the consequences of the behavior of a so-called electron on a computer screen or on a photographic plate or on a sensor somewhere, but the electron itself is just an abstract theoretical entity. All we can assert is that nature behaves as if electrons existed. Nature behaves as if electromagnetic waves vibrated in a complete vacuum. Nature behaves as if atoms had a nucleus composed of protons and neutrons, but, according to anti-realism, these are not literal entities, these are metaphorical entities. In my own philosophy, I use an aquatic metaphor.

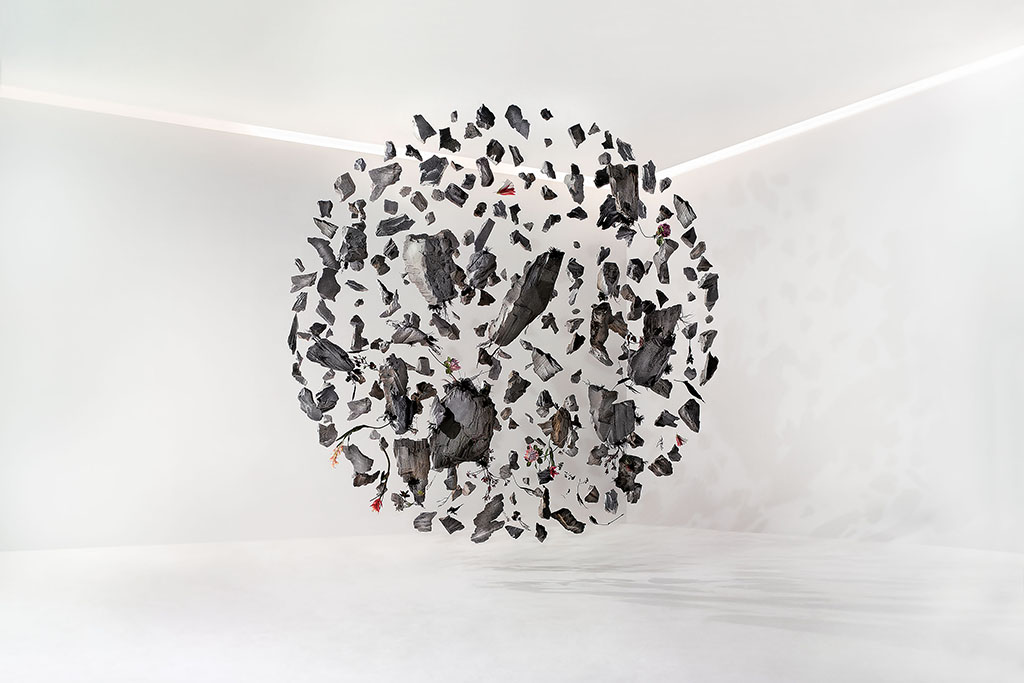

Whirlpools… You talk about drops and oceans; I like to talk about whirlpools in the stream. I think that we, as living creatures, are like whirlpools in a stream. Whirlpools are processes of localization in the flow of water, right? You can point at the whirlpool and say “here is a whirlpool.” You can delineate its boundaries. Yet there is nothing to the whirlpool but the stream itself. It’s just water in movement, not a separate entity. It’s just a local pattern of behavior of the stream and I think that’s what living beings are, local patterns of dissociated behavior of universal consciousness. You can point at a living being and say “look, here are the boundaries, here is me, there I am,” and you can trace the boundaries of a human body just like you can trace the boundaries of a whirlpool. Yet, according to my metaphor, there is nothing to the whirlpool but the stream: universal consciousness. In that sense, the ego and universal consciousness are not separate. The local pattern entails dissociation, this illusion of separation between the ego and the rest, the lover and the Beloved. And it’s intrinsic to the nature of consciousness that, when it becomes dissociated from an aspect of itself, it misses that which is no longer available to conscious acquaintance and the missing of that and the consequent feeling, could be called love. The lover yearning for the Beloved is a direct consequence, in my metaphor, of the dissociated whirlpool longing for the rest of the stream. It forgets that there is nothing but the stream itself. The moment the dissociation is over, the “lover” reencounters the “Beloved.”

Now, this implies “heart,” or feeling, an emotional relationship between lover and Beloved. In materialism, emotion is not considered to be a critical part of the philosophic experience. But there is specific emotional content in the relationship between self and universal consciousness—a yearning—and this suggests a correspondence, it suggests a means of communication almost. I understand you. Our emotions are integral to our psychic faculties and by trying to carve them out and throw them away we are mutilating ourselves. Why are we going to handicap ourselves by committing emotional-mutilation? It’s like cutting off a leg or an arm and expecting it to be as efficient as if we hadn’t done that. It’s nonsense.

That’s my point, we live in an emotional/feeling experience and without it there would be no experience of a living context. I think emotion ultimately drives everything, and I don’t mean only human history. I think the force we call emotion might drive the process of dissociation at a universal level. In the process of forming ‘whirlpools,’ there might be an inherent yearning for an ‘other’ because if there is no dissociation, no whirlpools, there is only the one stream. There is no other, and the emotional force—loneliness?—associated with that may be so strong that it ultimately creates a process of dissociation. Once that process takes root then you have, in turn, the longing for what has been lost…

Okay. …the yearning for the other part of self that is now separated from Itself, and this drives philosophical movements, religions, everything.

So, without the longing, the yearning, there would be no expression of need or desire, there would be no spirituality, no Vedas. It’s a profoundly important point. But how do you account for the presence of feeling and its sensory impact within consciousness and the brain? I see all experiences as excitations of consciousness and the metaphorical images of that.

Emotional experiences are closest to the innate dispositions of consciousness. In other words, they reflect pure psychic energy, the motivational drive that makes consciousness vibrate or get excited in the first place.

Including the emotional? Surely.

Okay. This is not often stated, Bernardo. Ultimately, emotions are phenomena sensed in consciousness, these are experiences, right? And there are different categories of experience. Some are perceptual, some intuitive, some intellectual, and some are highly emotional. There is a feeling aspect to certain experiences that could be pure emotion. But I do see them all as excitations of consciousness. Different chords or tones. Emotional experiences are closest to the innate dispositions of consciousness. In other words, they reflect pure psychic energy, the motivational drive that makes consciousness vibrate or get excited in the first place. They are the first level of differentiation from a purely non-excited consciousness, if the latter can be said to exist. Emotion is the first manifestation of pure potentiality and it reflects primordial drives, the primordial energy that gets everything into movement. But it’s nonetheless still an excitation of consciousness in so far as we only know it because we experience it.

It would seem that this feeling of loss and longing, this yearning, is fundamental to the human condition. Sure. Most human yearnings are yearnings to transcend limitations, the limitations inherent to the human condition. In other words, the limitations we have as seemingly separate beings. What is adrenaline-seeking behavior, for instance, but an attempt to transcend the limitations of the human condition? So yes, I am with you that yearning is behind everything and it expresses itself in many different words, tonalities, colors and forms, but the underlying force is the same.

It’s almost layered in that… Absolutely…

… layers of yearning are interconnected states encompassing the needs and desires for everything from the basic to the profound. And as you go through those layers, those states, then the desire for material stuff diminishes, becomes less satisfying? Materialism does not survive direct experience of transcendence.

I’ll quote that…[laughs] So, whoever is a materialist has not had that direct experience yet. That’s for sure.

Consciousness also often infers a wide range of feelings and positive human attributes associated with it: compassion, empathy, intuition, kindness, joy; could we say that consciousness is inherently a “good thing” with regard to its own behavior? The list of associated states that you just made—compassion, empathy, intuition, kindness, joy, love, these are all positive experiences, positive feelings, positive values, so to say. And I think they all exist, of course they all exist, we experience them, but I think they are not any less valid, in the sense of not being any less real, than anger, sadness, frustration, despair, angst and the whole gamut of what we call negative feelings, negative emotions. But let me clarify one point. My original point was that normal patterns of brain activity correspond to dissociation in universal consciousness, the whirlpool in the stream. If that dissociation were to reduce so that we would become more conscious of what is beyond the boundaries of our personal self, then those normal patterns of brain activity should be replaced with reduced brain activity. So if dissociation reduces, then brain activity should reduce as well, and it turns out that scientifically, empirically, that’s what’s observed. But this is all completely agnostic of the kind of experience that you have, whether it’s compassion or anger, whether it’s empathy or hate—these are all experiences, mental activities whose extrinsic appearance is certain patterns of brain activity. The latter are what the experiences look like from a second person perspective; in other words, from across the dissociative boundary. So I was very agnostic of positive and negative when I made that analogy. I am not sure that negative emotions are any less or more conducive to dissociation than positive emotions.

Despite the shortcomings of religious institutions through the ages, religion was humanity’s way to give words to an inner intuition, an inner perception of what is real.

Isn’t there a different kind of coherence to a state of meditation as opposed to a state of negative emotional excitement? What I can say is this: the moment I make this analogy between experiences and excitations, or vibrations of consciousness, I’m opening the door for consciousness to exist without experience. In other words, if experiences are like the vibrations of a guitar string, then nothing stops the guitar string from existing even when it’s not vibrating. Experiences are nothing but consciousness in motion, so consciousness may exist without experiences. And I think that’s what you’re driving to in a state of meditation; that you eliminate the excitation, reduce the vibrations. You meditate to experience the string itself. But if the string were to stop completely and be in absolute repose, then nothing would be experienced. So the fact that people can reflect on the great void in the Buddhist tradition for instance, or refer to accounts of pure consciousness that recur in all traditions of the world, they cannot be talking about consciousness in absolute repose because there is nothing to say about it. Perhaps what is happening is that they experience a fundamental tone, a single vibration, a carrier wave, if you will, of universal consciousness, which is always there underneath ordinary experiences.

The om. Exactly. An om that’s intrinsic to the string, and all other experiences are modulations of that basic tone, and if you remove the modulations, then you are left with that om. I think that is experienceable, because it is inherent to all consciousness, including the dissociated guitar string, including the dissociated whirlpools, lover and Beloved. It’s a consummate force. That’s what is experienced in deep states of meditation, but it’s completely neutral morally speaking, ethically speaking. It is not good or bad, it’s not positive or negative, it’s just the fundamental vibration of existence.

Is the sense of longing for life after death one of the planks for belief systems that seem to manifest around concepts of consciousness? I think that’s undeniable, right? And the risk of wish fulfillment and self-deception in that is obvious, it’s blatant, and one has to be very self-guarded against this kind of wish for personal immortality. But this is not the most important point. Today we are exposed to the much larger risks associated with a mainstream metaphysics that has made this amazing assertion that consciousness ends. Consciousness is the very ground of reality. Positing that it ends, is, historically speaking, an anomaly. It’s surprising. It’s abnormal. It’s an aberration. But, okay, that’s the status quo, the narrative that leads most people on the street to lose their source of meaning because they live in a cultural ethos that denies the endurance of consciousness. The concept of universal consciousness, mind, god, reflects an intuition of something real. And that’s the origin of the god concept. It wasn’t a wish fulfillment manoeuvre. Despite the shortcomings of religious institutions through the ages, religion was humanity’s way to give words to an inner intuition, an inner perception of what is real.

So, finally, there is a principal philosophic question utterly rejected in materialism: is there a purpose to consciousness, or to God? What you’re saying is that death is a kind of deconstruction and a return to universal consciousness, but what’s your view on the existential purpose of “consciousness”? Technically we call it telos—the idea that nature is guided by intent, that it’s not just random. Nature doesn’t necessarily have a complete picture of its final state but it nonetheless operates teleologically, operates with intent; it’s trying to get somewhere. I think life is a vehicle on that teleological path. Life has many negative aspects; it’s dissociation, after all. The lover loses the Beloved; they become separated through a dissociative boundary. But at the same time, living beings have the unique capacity of metacognition, the ability to self-reflect. I believe universal consciousness does not have the capacity to develop its own metacognition without these reflective, dissociative states. Life—dissociation—may thus be required for consciousness to become aware of itself, and this may be the purpose and meaning of life.

You seem to see consciousness as an evolving thing… I have to be careful here. It’s an evolution in the sense that it’s getting to know itself. But it’s not changing in the sense that it becomes something other than what it is and has always been. It’s just actualizing its potential for knowing what it is, has always been and will always be.

[/wcm_restrict]

PHOTO © VIVID CAFE | BIGSTOCKPHOTO.COM

PHOTO © PUBLIC DOMAIN

PHOTO © BALAZ5 | BIGSTOCKPHOTO.COM

PHOTO © CYMATICS.ORG

RETURN TO ISSUE 96 TABLE OF CONTENTS

[/wcm_restrict] [wcm_nonmember]

To read this article in full, you must Buy Digital Subscription, or log in if you are a subscriber.

[/wcm_nonmember]