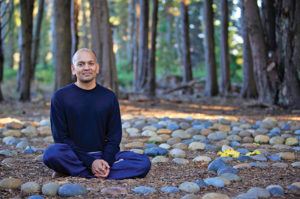

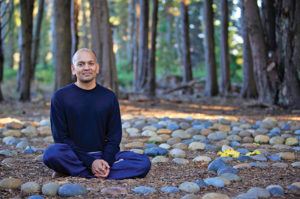

A CONVERSATION WITH NIPUN MEHTA

A CONVERSATION WITH NIPUN MEHTA

Interviewed by Russell Leung and Rita Fabrizio

We believe in the inherent generosity of others

and aim to ignite that spirit of service.

Through our small, collective acts,

we hope to transform ourselves and the world.

—Nipun Mehta

At the age of 12, Nipun and his family left India to live in Santa Clara, California. He received his computer science/ philosophy degree from the University of California at Berkeley, and began his career working for Sun Microsystems in Silicon Valley. Utilizing his technology background, Nipun began his experiments in giving by co-creating an online, spiritually based, humanitarian community called ServiceSpace, with its focus on small acts of service that “catalyze inner and outer transformation.”

In 2005, Nipun and his wife, Guri, went on a walking pilgrimage across India, performing small acts of kindness “with great love,” and living on $1 per day. Today, they live in Berkeley, California, and ServiceSpace has grown into a global multi-faceted ecosystem working to “create a shift from consumption to contribution, transaction to trust, scarcity to abundance, and isolation to community.”

NIPUN MEHTA… “Two, three weeks ago we just had Karma Kitchen in Krakow, Poland, which is twenty minutes from Auschwitz, which is where Schindler’s factory was. They never had anything like Karma Kitchen in that place.”

RUSS LEUNG: What about education? Can you train people, teach people to become compassionate and generous? Have you developed a workshop, an educational program for that purpose? Yeah, so a lot of people come to us and say, hey what you guys are doing is beautiful, what ServiceSpace has done unimaginable, unexplainable, but I love it. My heart is awakened; I want to bring this into my context. Maybe I’m in government, maybe I’m in the private sector, maybe I’m in a family, maybe I’m in the medical field, maybe I’m a teacher… I want to bring this here. Can you help me? And, what we would say is that I wish it was cut-and-paste, because here you go, right? If it was just in the field of matter, then I could just give it to you. But it has to be awakened. Like there’s an element within you that needs to be activated for this to make sense on the outside.

We formed the first one with six people, and three “anchors.” And what we tell our anchors is that their job is not to help people find answers, but to actually help them hold the question. So it’s very different. They’re sort of in the back themselves—they are modeling that—then what happens is those that finish a Circle, they’ll come back and they’ll say, I want to volunteer to be an anchor. And so then they support the next people. And there are all kinds of people, there are people from nineteen counties that have done this. And most recently, now, there are themed Circles. With people that are just in business, or people who are just in medicine. They come together and say, look, I can use a little bit of this humanity; I could use this inside-out approach. The most recent one that we just completed two weeks ago was business. One guy was a Russian billionaire, he kind of lost it all, and he says, this whole cycle is not really for me—I want to know how to create a kind world; how do I create systems around that? And so he joined the Circle! … One of the volunteers was actually somebody who was Obama’s lawyer in his first term: Obama’s General Counsel. And she came and she said, I know how. I’ve been taught how to climb up the ladder, but I actually want to learn about how to hold space from being in the back.

SUBSCRIBE TO READ FULL CONTENT

EDITORS’ NOTE

EDITORS’ NOTE ALWAYS PART OF SOMETHING LARGER

ALWAYS PART OF SOMETHING LARGER  CHANGE YOURSELF

CHANGE YOURSELF JUST BE

JUST BE  THE PATH ACCORDING TO A SUFI POET

THE PATH ACCORDING TO A SUFI POET THE ART OF UBUNTU

THE ART OF UBUNTU MY MOON

MY MOON

FEATURED ARTIST

FEATURED ARTIST

There are times when we find ourselves shrinking from life, from beauty, from the truth. From the story of love unfolding all around us, and within ourselves. It often happens in the moments where we allow the mind to transport us; when we allow the material world and language to determine the limits of our understanding and experience. As Mark Nepo describes, these tendencies can construct a prison of our own making, within which only sorrow and sadness grows.

There are times when we find ourselves shrinking from life, from beauty, from the truth. From the story of love unfolding all around us, and within ourselves. It often happens in the moments where we allow the mind to transport us; when we allow the material world and language to determine the limits of our understanding and experience. As Mark Nepo describes, these tendencies can construct a prison of our own making, within which only sorrow and sadness grows. A CONVERSATION WITH NIPUN MEHTA

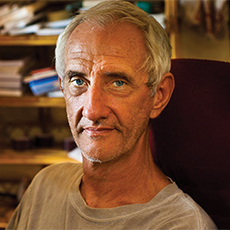

A CONVERSATION WITH NIPUN MEHTA A CONVERSATION WITH DAVID GODMAN

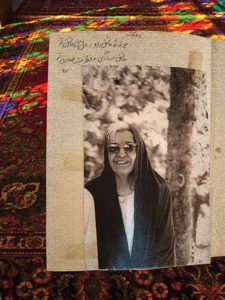

A CONVERSATION WITH DAVID GODMAN MEHRI HABIBI PARSA 1931-2017

MEHRI HABIBI PARSA 1931-2017 A Discourse

A Discourse by Mary Gossy

by Mary Gossy by Jawid Mojaddedi

by Jawid Mojaddedi